A Virtual Tour of the Old North End, Part 1

- Connor Flanagan

- Mar 9, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 26, 2022

On Thursday, April 29th at 11am author and historian Anne Halsey will be giving a lecture live on Zoom detailing the interesting history of Southampton's Main Street through the stories left behind by those who lived there. Including some of Anne's own relatives. To RSVP for her talk please click here!

The blog entry below comes directly from Anne as an early look at some of the info she will talk about in her virtual talk in April.

Also if you're interested, you can buy your very own copy of "In Old Southampton" from our online store if you click here!

by Anne Halsey

For the first eight years of the Southampton settlement, the Puritan “undertakers” made their homes at the head of Old Town Pond, near the present site of Southampton Hospital. In 1648, they moved the settlement about three-quarters of a mile west, establishing the South End and North End of the town and began clearing lots and building houses along the south end of Ye Towne Street. According to former Southampton Town Historian, Abigail Fithian Halsey (1873-1946), the “long Main Street of today, winding from the ocean to the woods, follows the general plan of Towne Street of 1648” with the sea “cast like a mantle” around the little town.

In 1651, John Jagger came to Southampton from Stamford, Connecticut, and was given by the town a fifty-pound lot in the new North End neighborhood, on condition that he would “use his trade to the best of his power for the use of the inhabitants.” His neighbors there soon included members of the Sayres, Johnes, Post, Halsey, Howell, Bower, Bishop, and Barnes families. Until 1664, when Job’s Lane was created, Jagger Lane was the only way residents could get around the swamp at the north end of Agawam Lake to their farms on the Great Playne.

Windmill Lane, part of the original town plan and then known as West Street, runs from the old swamp land north of Agawam Lake and intersects with North Sea Road and Bowden Square, in what is the heart of the Old North End. Around 1713, windmills, which ground the grist for the town, stood at both ends of Windmill Lane. According to Abigail Halsey, the “first recorded schoolhouse probably stood in the West Street [Windmill Lane], opposite Jagger Lane and south of the present North End Graveyard. After 1683, it housed the county courts as well as the village school.”

By the 19th century, the North End was a close community of primarily established families who held strict religious beliefs, coupled with superstitions and customs gleaned by years of seafaring. And they weren’t particularly welcoming to newcomers. Helen Halsey Haroutunian (1914-2003), in her introduction to the collection Incident on the Bark Columbia, letters between Southampton whaler Captain Samuel McCorkle and his neighbor Charles Halsey, a farmer, “In the early 1820s, James McCorkle of Scotch-Irish descent, settled in ‘the Old North End,’ a seeming-nice neighborhood of Southampton, Long Island. The simple farming community revealed to the pioneer in a new land few aristocratic symptoms. Probably, his wife and daughters discovered sooner than he that ‘the Old North End’ was less a geographic neighborhood than a spiritual one possessed by a few families who reckoned back to 1640” and marked by an “indefinable local chill.”

Among the families who lived in the North End in the 1800s were the Hunttings, at 126 North Main, who lived just north of the old Town Hall in the 1698 home built by Isaac Bower, with a circa 1650 cellar dating back to the original house. Next door were the Posts, builders of the Old Post House, a hotel and boarding house, which, as Mary Cummings has pointed out, was originally a farmhouse built in 1684. Across the street, at 159 North Main, on the northwest corner of North Main Street and Jagger Lane, lived the legendary Southampton whaler and goldrusher Captain George White on the property formerly belonging to John Jagger, in a 1699 farmhouse, which still stands.

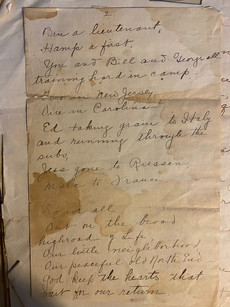

Handwritten copy of Abigail Fithian Halsey’s poem “Neighbors"

At 17 North Main Street is the famous Herrick house, where, during the British occupation of Southampton in the winter of 1778-1779, General Sir William Erskine took his meals. A few doors down at Number 49, among a cluster of homes originally belonging to various members of the Halsey family, is the house Captain Henry Halsey (captain of the local militia following the War of 1812, and not a sea captain as were both of his brothers and most of his neighbors) built in 1833. That is, he re-built an old house that was standing somewhere on the property, very likely farther south, in what was then the orchard. All the old beams in the cellar show mortise marks where they had been previously used.

My great-grandfather Reverend Jesse Halsey (1882-1954), was born in the birthing room at 49 North Main and raised in Southampton during the years in which the town changed from an isolated New England village into the “the queen of America’s watering places.”

While Southampton was transforming into a coastal resort, the North End remained a tight-knit community of modest, hardworking families—farmers, merchants, fishermen, tradesmen, teachers, midwives, and clergy. “The town was growing; first by a few summer boarders, then by a substantial influx of summer cottagers (Yorkers as we called them),” Jesse Halsey wrote. “Naturally some permanent residents were added. Among these was a Scotch family of size; the father was a skilled plumber and soon came to affluence, but in the first year they lived in the back street, as we who lived on Main Street called it. Its real name was Windmill Lane because in the old days three windmills were on or near it; I remember one of them, Cap’n Bill White’s. Well, the Cameron boys, one bigger than me and one younger, soon joined our gang and were often on our place where the crowd ‘hung out’ playing around the haystacks or on rainy days in the big barn.”

He recalled that the windmills disappeared gradually after the Town Water Works were built, the trenches of which were all dug by hand. “The pumping station was [in the] North End of the Village. At first it was a pneumatic system, there was no standpipe as at present. In case of fire, the air pump was started and pressure pushed up. Everyone was very proud of the quality of the water—'it never saw the air till it reached your faucet.’ Some of the city people had it bottled and sent to their New York homes. One enthusiast took a supply on a shipboard to Europe with him!”

Writing his memoirs in the 1950s, Reverend Halsey paints a picturesque and moody scene of the old North End neighborhood in the late 1890s:

Main Street wound through the village, cow-path fashion and was lined with trees, stately elms and maples mostly, but in front of our place there was a variety for Capt. Harry (grandfather), when he had moved out from the city brought catalpas and ailanthus ‘the tree of heaven’ ('stink trees’ we boys called them in private though that word along with ‘belly’ and other Scriptural vocables was taboo in public).

Some of the ailanthus blossomed in June, and mother would boil the buds to spray her roses. There was a great brass kettle of the decoction in the woodshed at the time she died. I was five then, and remember little about her save several outlandish things like that; and a big bottle of asafetida remaining from the old doctor’s treatment of her pneumonia. I’d go and uncork it and take a whiff of the awful stuff and wonder why it shouldn’t have killed her!”

We lived in a story and a half house on the main street in the North End of the village, a mile and a half from the ocean. When the wind was south the surf was always in our ears and as in most places, the weather was a constant subject of conversation. Sailor’s rhymes such as: ‘Red sky at night, sailor’s delight; Red sky in the morning, sailor take warning,’ were quoted even by the children. Older folk had more elaborate signs, for example, my father always stoutly maintained that if the sun went down clear on Friday night it would rain by Monday morning.

Grandfather, with his two brothers, had been apprenticed to a mason in New York City, where they built many of the buildings in Greenwich Village (1820-30) and on Canal Street. Some of these are still standing; one on Grove Street has the identical trim and fireplace and mantle as that in our Southampton house which grandfather acquired when business reverses in 1832, drove him back to the country. He bought a farm, with the help of an unpopular brother-in-law, and rebuilt an old house Cape Cod style. Forty years ago, I raised up the old lean-to kitchen and superimposed another story with a gambrel roof so that the house is now half Dutch and half English—like historical-geographic Long Island itself.

The house sits (or stands) close to the road on a lot that in my boyhood measured ‘a small acre.’ It was flanked on the north by a big grey-shingled barn, very old and much patched, but tight. Between the barn and house was a big ‘cow-yard’ with sheds and chicken houses. West was the shop and carriage house and pig pens, backed in the fall and winter by numerous stacks of corn-stalks and meadow-hay. A corn-house and big wood pile adjoined. With the farm lots scattered here and there all within a short mile, these constituted an all but self-sustaining economic unity. Grandfather carried on his mason’s trade with an indifferent zeal, but entire success, in the village, but the farm furnished the living.

A large orchard to the south of the house furnished shade and apples of indifferent quality: Baldwins, Pippins, and Russets. Several grape vines, seldom pruned, found their luxurious way over the treetops—their roots were in the cow yard—and furnished an abundant supply for eating and for jelly. In September, I’d come home at noon from the nearby school and go up in the tree like a monkey, eating great quantities—unwashed—seeds and all. (Other monkeys, my playmates, often accompanied me.)

The old cemetery lay between our house and the first store. At night when I had to run errands, I would get in the middle of the street, unless it was deep with mud and run as fast as I could. The house next to ours was occupied by an eccentric old lady, the widow of a sea captain long since dead, and the place was terribly overgrown. Opposite hers was an elegant white mansion, the result of whaling prosperity but now deserted and overgrown so that the street was a dark tunnel leading to the light shining in the window of Seely’s store.

Beyond the spooky house of Captain Jagger was the home of my playmate and lifelong friend, Jack Herrick. Mr. Herrick had a hardware store and put a lamp post on the triangle that extended south of their house just in front of the cemetery. A street lamp of the newest design (1890 circa) sat high on its post, new and shining green. Jack and I were commissioned to light it for the first time when it got dark. We were told by the adults that ‘You’ll never be rich if you use more than one match.’In my next post, I’ll share the history of the North End schools, as well as the first town library—it was housed in a kitchen!