Rogers Mansion - Historic Structure Report, 2017

- Connor Flanagan

- Aug 4, 2020

- 53 min read

Updated: Aug 26, 2022

Below we have the Rogers Mansion Historic Structure Report that was done in 2017 by Sally Spanburgh. This is probably one of the most important documents in our collection as it is a great place to quickly find information on the Rogers Mansion and its previous owners, one of the most important topics to us here at the Southampton History Museum.

I have used this as a reference while doing research on various projects over the years from my lecture on the Rogers Family earlier this year to some of my education programs with our local school children teaching them about the history of whaling captains in Southampton. This is also an extremely important document when it comes to any construction projects that may come up in the future so we can reference how old certain parts of the building are and if we are doing any restoration work, how best to go about it.

And beyond its importance to us for research and grant writing purposes, it is just a really interesting document if you are a fan of old buildings and local history. You can download a PDF copy for yourself if you want to or scroll down and read through this digitized version. Enjoy!

Download link

“He is no fool who gives what he

cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose.”

- J. Elliott

Acknowledgements

The compilation of this report would not have been possible without the amount of available resources online and the assistance of many: Beth Gates, Yvette Postelle and Tony Valle at Southampton’s Rogers Memorial Library, Eric Woodward’s postcard collection, Skip Ralph, Paul Rogers, the Bridgehampton Museum, Janet Dayton, Guy Rutherford, the Suffolk County Clerk’s Office, Chris Gaynor, Richard Warden, Bob Hand, the staff of the Southampton Historical Museum and their Archives collection.

Architectural plans and elevations measured and drafted by Richard Warden.

This report was made possible in part by a New York State grant offered through Preserve New York. Preserve New York is a signature grant program of the New York State Council on the Arts and the Preservation League of New York State, with generous support from The Robert David Lion Gardiner Foundation. Preserve New York is made possible with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

Maps

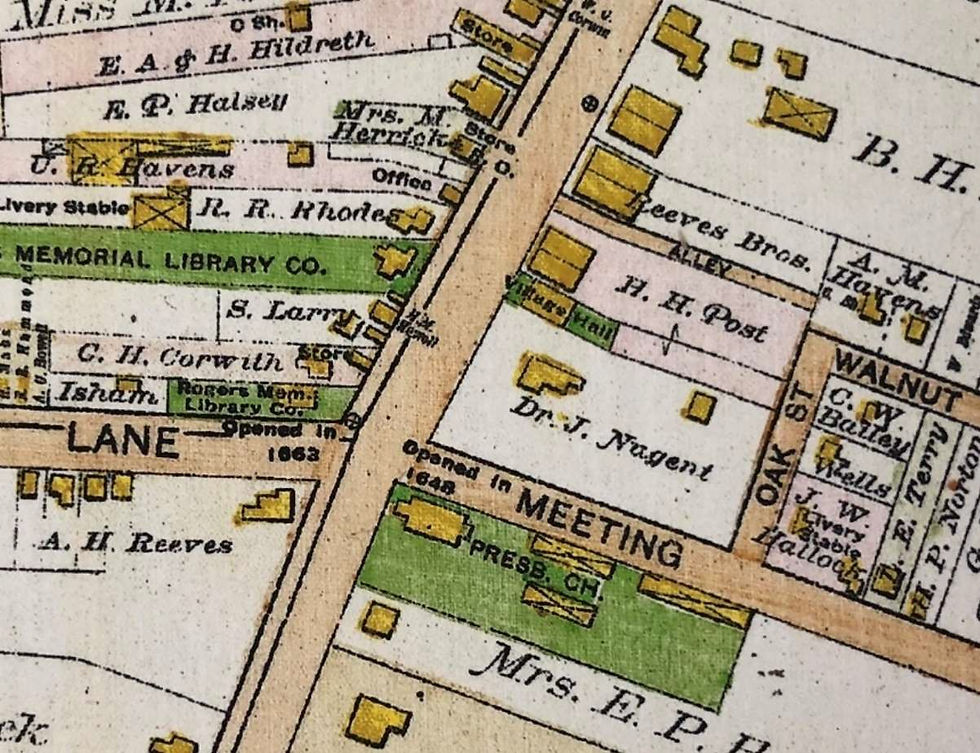

Detail, Smith and Chase Wall Map of Suffolk County, Long Island, 1858.

Detail, Plate 185, Atlas of Long Island, Beers, Comstock & Cline, 1873.

Detail, Map of Main Street, by William S. Pelletreau, 1878. Courtesy of the Suffolk County Historical Society.

Detail, Atlas of Long Island, Plan of Southampton, F. W. Beers, 1894.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Detail, 1895

Detail, Plate 24, Atlas of Suffolk County, Long Island, Vol. 1, Ocean Shore, E. Belcher & Hyde, 1902.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Detail, 1905

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Detail, 1909

Detail, Plate 23, Atlas of a Part of Suffolk County, Long Island, New York, South Side – Ocean Shore, 1916, Vol. 2, E. Belcher & Hyde.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Detail, 1916

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Detail, 1926

Detail, Plate sc193012f1, Long Island Black and White Aerials Collection, 1930, Stony Brook University.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map Detail, 1932

Detail, U.S. Army Air Corps Aerial Imagery Taken of the Southern Coast of Long Island, June-July 1938.

March 2016 Aerial View, courtesy of Bob Hand.

Rogers Mansion—Vintage Images

Above: Rogers Mansion about 1890 (SHHM). Notice the front porch stair that extends the full width of the porch, the absence of the second floor center bay window, the entry door without an upper glazed panel, the six-over-six double-hung windows on the first story, the shuttered clearstory windows, the dentil moldings on the Cupola’s cornice, the stone foundation, and the original layout of the windows on the south elevation.

Below: The Rogers Mansion about 1895 (SHHM). Notice the original layout of the windows on the north elevation and the pres- ence of a dormer on the north side of the 1780 wing.

Above: The Rogers Mansion about 1898, courtesy of The Eric Woodward Collection. Notice the absence of the south chimney, the seven-sided south bay projection and the shed dormers on the 1780 wing.

Below: The Rogers Mansion about 1900 (SHHM). Parrish and a young girl are pictured in the side yard. Notice that the southwest first floor window has been replaced, and Parrish has yet to make any significant exterior changes since his purchase of the resi- dence from the Nugent family.

Above: The Rogers Mansion about 1926, in preparation for being moved 100 feet back (SHHM). Notice the several north and south additions, the alteration of the main entry door and the replacement of the four first floor windows.

Below: The Rogers Mansion about 1928, after being relocated (SHHM). Notice the presence of window awnings and the narrower stair up to the front porch.

Architectural Drawings

***citations will be marked in brackets after the sentence where the reference takes place and will be marked in red in lieu of proper footnotes not being possible in this digital format***

Introduction

The Rogers Mansion lies in the Incorporated Village of Southampton, in the Town of Southampton, County of Suffolk, Long Island, New York. It’s original street address was along Main Street, rather than Meeting House Lane, before it was moved one hundred feet back in 1927.

The Town of Southampton was settled in 1640 by English Puritans who left Connecticut to escape religious persecution. Main Street is one of the first roadways created in the township dating back to the mid-17th century and to the settlers’ second settlement area (the first having been around a smaller pond to the east rather than the larger “Town Pond” known today as “Lake Agawam”). The original settlers became an entity known as the Town Proprietors who purchased “all the territory east of Canoe Place and west of a “place or plain called Wainscott,” from Native Americans. “This tract was therefore owned by them as undivided property, and the share that each possessed was in proportion to the amount paid by him. If a person who was acceptable to the majority of the inhabitants wished to settle in the town, a home lot and farm was frequently granted to him, generally, however, with the condition that he was to remain and improve the same for a term of years.”[Southampton Town Records, Vol. 1]

The entirety of this second settlement area was laid out by the settlers in 1648 into “house lots” usually three to nine acres in size. The homes were located fairly close to one another, and besides them there was only one other building, a central community meeting place that functioned as church, courthouse, school, and hotel.

Meeting House Lane is also an old street, opened in 1648 as the route leading those from the east to the “meeting house”. In 1707 a church structure was located on the subject property at its very southwest corner (the northeast corner of the roadway intersection, having been moved there from originally being situated further south along Main Street), and in 1843 the present First Presbyterian Church of Southampton was built on the opposite corner (southeast corner of Main Street and Meeting House Lane), where it survives today.

Summary History of the Rogers Mansion & Property

The Rogers Mansion property was owned by the family and descendants of William Rogers from 1650 to1889, a span of 239 years. During that time the property was about nine acres in size and the house was altered at least twice.

From 1889 to 1899 the property was owned by Dr. John Nugent and his family as his medical career blossomed. During the Nugent ownership the property was reduced in size to four acres and the house was enlarged.

From 1899 to 1943 the property was owned by Samuel L. Parrish and his heirs. During that time the mansion was altered significantly but the property remained the same size.

Since 1943 the property has been owned by the Incorporated Village of Southampton, and since 1952 it has been stewarded by the Southampton Colonial Society (aka Southampton Historical Museum). Several historic accessory buildings have been relocated to the property since then which are not a part of this report.

Rogers Family Property Ownership 1648-1889

William Rogers (abt. 1606-btwn. 1658-1667)

William Rogers was allotted the subject property from the Southampton Town proprietors in the mid to late 1640s. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 1, page 48, officially record the transaction in September 1650 but some suggest it may have occurred in 1648.] He was an early settler of Southampton and the first of the Rogers family name to arrive in the township. He was born in Leyden, Holland to English parents. [There are many, many William Rogers family trees that have been published. Some of them suggest he was born in England. This document is based upon a genealogy that appears to be the most well-researched, published on the Long Island Surnames website, Family ID F5142, also published in The American Genealogist, Vol. 10, No. 1, July 1933. This research also states that the subject William Rogers has never been successfully proven as a son of Thomas Rogers, the Mayflower pilgrim] He was raised in England, a middle child of at least four other siblings, and married Anna Hale (1612- 1669) about 1630, beginning a family shortly thereafter.

“He first appeared at Weathersfield, Conn., where he owned five pieces of land before a general registration in 1640 …Rogers is not again noticed until 1644, when he is found at Southampton, Long Island. He was one of the earliest settlers there and was probably there before 1644. [George Rogers] Howell says he was there in 1642…He was a freeman at Southampton on March 6, 1649 [As freeman, one had full political and civil rights.], and can be found in that town until 1655, although he appears to have lived for a few years previous to 1649 in Hempstead [Long Island]. After 1655 his son Obadiah Rogers, is found occupying the house that William had in Southampton…It is generally assumed that William turned his home over to his son Obadiah and removed to Huntington [Long Island] with the remainder of his family.” [From longislandsurnames.com, from The American Genealogist, Vol. 10, No. 1, July 1933.]

William Rogers was only sporadically present in the Town of Southampton for a period of about ten years. He owned property throughout the township and was involved in the laying out of large areas of land as well as in the general administration of town business. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 1] He was also a significant participant of the early settlement of Huntington, Long Island.

William Rogers (1606-btwn 1658-67)

(m.1630) Ann/Anna Hale/Hall (1612-abt. 1669)

Obadiah Rogers Sr. (1633-1692)

John Rogers (1636-1707)

Mary Rogers (abt. 1638)

Samuel Rogers (abt. 1640)

Hannah Rogers (b.1644)

Noah Rogers (abt. 1646-1725)

Thomas Rogers (abt. 1657)

The precise original appearance of the William Rogers homestead is unknown but there are resources from which to draw reasonable theories: known early local homesteads, and the architectural components and design of the present structure.

Framing that predates the 1843 construction date of the principal western volume is present within this timber-framed structure. The size and shape of this volume is also similar to earlier local homes. Southampton’s earliest homes were predominantly two-story, saltbox, or Cape styles, depending on the means and/or cultural exposure of the owner. Rogers’ wealth is unknown but as he traveled extensively and was both an early settler of Southampton, Long Island and an original settler of Huntington, Long Island, it is assumed he was of ample means. Being raised in England and then spending equal amounts of time traveling west from Massachusetts to Connecticut, it is anyone’s guess which style he was more inclined to commission. The careful analysis of the subject building’s structure and available historical maps, however, appear to indicate that the first William Rogers homestead was a street-facing two-story structure.

While many early homes are known to have faced south in order to take advantage of southern sun exposures year-round, some of the earliest houses along Main Street responded to the design of the settlement area by formally acknowledging its layout. This early choice of orienting one’s house toward the street or toward the sun may also have reflected the owner’s occupation (farming, etc.).

“From the beginning, as soon as substantial houses were built, they took the East Anglican form. First and foremost, all were wood houses…The ubiquitous saltbox form of house in New England had precedent in East Anglia and Kent [England]. Likewise, the Cape Cod-style one-and-a-half-story house also had precursors in the same region…These house types were built in different sizes and elaborations. Some were simple one-room structures, more an accommodation to modest budget than familial need, which could be easily added to…Interior arrangements around the central chimney stack followed an English pattern as well: a small central entryway…with a three-run “dog leg” stairway before the chimney stack leading to chambers above. To the left and right of the entry were two large rooms. One was a hall, a holdover from the medieval hall, which was the center of all public life in a manor house. It served as kitchen and great room. The other was the parlor, a room of formality, which was reserved as the owner’s bedchamber but also reception room on high occasions. From this plan the New England house expanded, usually first with a one-story extension across the entire back for a kitchen (the hall retaining its dining function), pantry, and dairy. Other extensions could be off the gable end(s) or to the rear (forming an “L” shape), all to accommodate more residents.” [Old Homes of New England; Historic Houses in Clapboard, Shingle, and Stone , Roderic H. Blackburn, Rizzoli, 2010.]

The Sayre House, no longer existing, was situated at the opposite end of the block as the Rogers Homestead, on the southeast corner of what is now Main Street and Hampton Road. Postcard image courtesy of the Eric Woodward Collection.

An early Halsey house on Main Street, located just north of where Herrick’s Hardware store is today. No longer extant. Faces the street. From “The Tercentenary of Job’s Lane, Southampton, Long Island 1664- 1964.”

The Mackie house, on South Main Street, built about 1733. Faces the street (east). Postcard image courtesy of the Eric Woodward Collection.

A late 1800s view of the Thomas Topping III House on South Main Street built in the late 1600s. Faces the street. Courtesy of St. John’s Church.

A typical 17th century New England house plan, from Architecture in Early New England, Abbott Lowell Cummings, 1984, Meriden-Stinehour Press, Meriden, Connecticut.

Evaluating the original position of the Rogers homestead on the property is also interesting: using historical maps to compare the building’s original location to other homesteads of similar construction dates appears to confirm the original structure’s date of construction but also reminds us that the house was on a larger lot than many others along the street and was therefore able to be situated more generously on its lot; a house on a narrow lot tends to be placed nearer to the street it faces than a house on a larger lot which tends to have a deeper front yard. The larger lot size and a house set further back from the roadway also contribute to an impression of wealth and social status.

Obadiah Rogers Sr. (1633-1692)

Obadiah Rogers Sr. is generally believed to have been William Rogers’ eldest son. He was born to William and Ann prior to the family’s arrival in the colonies about 1635. He was among at least six other siblings. He married Mary Russell (b.1634) in 1654 and had seven children. Like his father, he was also actively engaged in the general administration of the Town of Southampton. He owned considerable amounts of property throughout the township, both inherited and acquired on his own, and held official positions such as Constable, Overseer, and Juror. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 1]

Obadiah Rogers Sr. (1633-1692)

(m.1654) Mary Russell (b. abt. 1634)

Mary Rogers (unknown)

Obadiah Rogers (1655-1729)

Sarah Rogers (abt. 1659-abt. 1689)

Elizabeth Rogers (abt. 1665)

Jonah Rogers (abt.1655-abt. 1734)

Zachariah Rogers (abt. 1670-abt. 1694)

Patience Rogers (1677-1708)

Obadiah Rogers Jr. (1655-1729)

Obadiah Rogers Jr. was the oldest son to Obadiah Rogers Sr. and mother Mary Russell, and a grandson to William Rogers. He was the first of the subject property owners to have been born in Southampton. He had six other siblings including at least one sister who died before reaching maturity.

Obadiah Jr.’s father originally left the subject property, including a barn with orchard, garden, shop, and tools, to his youngest son, Zachariah, upon his death but Zachariah died unmarried and without children only two years after his father’s passing. Therefore, the property passed to the “next male heir”, Obadiah Jr., as stipulated in the terms of his father’s will.

Obadiah Jr. married Sarah Howell (b. 1663), of Southampton, in December 1683. She died around the time of the birth of their only child, daughter Irene, who also died in 1685. Obadiah Jr. next married Mary (Lupton) Clark, a widow, and together they had four children, two that died young, a surviving daughter, Mary, and son, Obadiah III.

Obadiah Jr. like his father and grandfather, was actively engaged in the administration of town business and a large property owner. According to town records, his most prominent role was as a trustee. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 2 and 3]

Obadiah Rogers Jr. (1655-1729)

(m. 1683) Sarah Howell (abt. 1663-1685)

Irene Rogers (b. 1685)

(m. aft. 1685) Mary Lupton (abt. 1660)

Sarah Rogers (unknown)

Deborah Rogers (unknown)

Mary Rogers (1686-1716)

Obadiah Rogers III (abt. 1699-1783)

The Rogers Homestead is assumed to have been architecturally unchanged from its original form during the first four generations of Rogers owners (William through Obadiah III). However, it is worth mentioning that in Obadiah Rogers Jr.’s will, he refers to the home’s cellar, indicating that it must have been considered either a valuable possession itself or filled with valuable contents.

Capt. Obadiah Rogers III (abt. 1699-1783)

Obadiah Rogers III was the only son and youngest child of Obadiah Jr. and Mary (Lupton Clark) Rogers. His sister, Mary, was thirteen years older and married in 1711, spending only twelve years alongside Obadiah growing up in the Rogers household.

Like his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather, Capt. Obadiah Rogers III was actively engaged with land acquisition and division [Capt. Obadiah Rogers III was an integral part of the laying out of the “30 Acre Division”, a tract of land lying between Mecox and Wainscott.] and in the general administration of town business. He held the prominent position of Town Clerk for several years, as well as Trustee, Overseer of the Poor, and Fence Viewer. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 3] He obtained his title of Captain by serving in the Revolutionary War; he was the Captain of a British schooner named the Brittania which was captured in May 1777 by the Connecticut sloop America captained by Asa Palmer. Capt. Obadiah married Abigail Herrick, of Southampton, in 1721. He and his wife had several children but only three reached maturity, leaving his small household at a manageable total of five (not including servants).

Capt. Obadiah Rogers III (abt. 1699-1783)

(m.1721) Abigail Herrick (1702-1782)

Stephen Rogers (b. 1722)

Mehetable Rogers (b.1725)

James Rogers (b. 1729)

Millicent Rogers (1732-1814)

Ruth Rogers (b.1734)

Mary Rogers (b. 1736)

Phebe Rogers (1739-1805)

Capt. Zephaniah Rogers (1742-1796)

Capt. Zephaniah Rogers (1742-1796)

Zephaniah Rogers was the youngest child and only surviving son of Capt. Obadiah and Abigail (Herrick) Rogers. Like his predecessors, he owned a lot of property and served his town; Zephaniah’s roles were as a Commissioner of Highways and a Constable. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 3] He was also a soldier in the Revolutionary War, rising to earn the title of Captain by 1776. Shortly after the war Zephaniah married Elizabeth Sayre of Southampton. They had six children together. According to census information there were nine household members in 1790: three males, five females, and one slave. Zephaniah died at age 54 in 1796. In his will Zephaniah left the subject property to his only son, Herrick Rogers, but the household continued to include his mother until her death, and his sisters until they married. [Zephaniah Roger’s Will is in the collection of the Southampton Historical Museum as well as the Suffolk County Clerk’s Office, Will Liber A, pages 507-508.]

Capt. Zephaniah Rogers (1742-1796)

(m. 1769) Elizabeth Sayre (1743-1814)

Huldah Rogers (1770-1815)

Herrick Rogers (1775-1827)

Susan Rogers (1783-1815)

Hannah Rogers (d. aft. 1796)

Abigail Rogers (d. aft. 1796)

Mary Rogers (d. aft. 1796)

During Zephaniah’s ownership of the Rogers homestead and property the residence was enlarged circa 1780, presumably due to the larger size of his family than of his predecessors. Evidence of this 1780s construct is pervasive in the 1780s volume, situated directly behind/east of the 1843 volume. During the repair of a water leak in October 2015, exterior wall framing could be seen confirming the 1780s age. The roof rafters and framing are also demonstrative of the late 1700s. Double-hung windows with twelve-over-twelve divided light patterns, and the rear stair contribute to the late 1700s construction date of this part of the evolving Rogers homestead.

Capt. Herrick Rogers (1775-1827)

Captain Herrick Rogers was the only son of Capt. Zephaniah and Elizabeth Sayre, and probably got his Christian name from his grandmother’s surname. In 1797 he married Hannah Rose, daughter of David Rose of the prominent Rose family of Southampton. Hannah’s sister, Nancy, married Micaiah (also Micah) Herrick, with whom Herrick Rogers formed a mercantile business named “Herrick Rogers and Co.” that was very successful. Auctions took place at the subject Rogers residence quite often. An appraisal of Capt. Herrick Rogers’ estate in the collection of the Suffolk County Clerk’s Office estimates its value at $4,000 upon his death – after taxes, etc., equivalent to about $93,000 today. He did not leave a will. Upon his death his entire estate passed to his second wife, Phebe. [Phebe Rogers’ will is in the collection of the Southampton History Museum.]

Conjectural Plans

Above: Conjectural layout of the original c.1650 William Rogers homestead.

Below: Conjectural layout of the c. 1780 Zephaniah Rogers house.

Herrick Rogers, like his male ancestors, was also a large land owner and served the Town of Southampton in positions such as a Commissioner of Highways and a Commissioner of Schools. [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 4] He served as a lieutenant soldier under the command of Abraham Rose in 1806 [Documents of the Senate of the State of New York, One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Session, “Military Minutes of the Council of Appointment of the State of New York, 1783-1821,” James B. Lyon, State Printer, 1901] and eventually received the title of captain. [According to the American Offshore Whaling Voyage database (nmdl.org), there was a voyage out of Sag Harbor in 1796 on the ship Hetty that traveled to Brazil and was mastered by a Rogers. Whether or not this may have been Herrick Rogers is unknown.] He was not uninvolved in sailing but purchased a sloop named Republican in 1801 along with his father-in-law, David Rose [The County Review, “Heavy Drinkers in Sag Harbor in 1820; Owners of Ships had Difficulty in Obtaining and Keeping Employees Sober,” Sept. 26, 1924.] which may or may not have been the British vessel formerly known as Polly captured by America in the late 1790s.

According to U.S. Census data, there were eleven people in Herrick Roger’s household in 1810 including three slaves (one who was named Aaron, released in 1817 [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 6]). Herrick Rogers and Co. also owned at least one slave collectively (named Cato, released in 1817 [Southampton Town Records, Vol. 6]), in addition to moveable and real property.

Capt. Herrick Rogers (1775-1827)

(m.1797) Hannah Rose (abt. 1780-1803)

Jetur Rogers (abt. 1800-1822)

(m. 1805) Phebe Sayre (1785-1842)

Capt. Albert Rogers (1807-1854)

Capt. Albert Rogers (1807-1854)

Captain Herrick Rogers had two sons, one with his first wife, Jetur Rogers, who died at the age of 22 in 1822, and another with his second wife, Capt. Albert Rogers. When Capt. Albert Rogers was 35 years old, he became the sole owner of the Rogers homestead when his mother died in 1842. At that time, he was married and had two children.

A portrait of Capt. Albert Rogers circa 1840, by Frederick Spencer, in the collection of the Southampton Historical Museum.

Albert Rogers received his title of captain as a whaler. He began whaling as a young man and became a master by the age of 28. For most of the nine-year period from 1835 to 1844 he was at sea whaling, almost always returning home with sperm oil, blubber, or bone. During that period, he purchased fire insurance for the Rogers property. The document in the collection of the Southampton Historical Museum describes the insured area as a “two story dwelling house & kitchen attached,” [The 1780s wing is 1.5 stories. Therefore, the 1780s portion must be being described as the attached kitchen, with the two story portion being that which was replaced or modified by the 1843 Greek Revival volume.] and the period in effect from March 26, 1840 to March 26, 1841. On the back of the document is written, “Permission is hereby given the written assured to build on a Milk house adjoining the kitchen attached to the said house,” and is dated April 14th, 1845. Two conclusions can be reached: that the fire insurance period had been extended, and that the tavern was a relic from Herrick Rogers ownership, as part of his mercantile business and related to the property being frequented by the public as a place where elections and auctions often took place.

In 1844, Capt. Albert Rogers retired from long-term offshore whaling voyages but did take part in 1849 in the California gold rush by investing as a trustee in the “Southampton and California Mining and Trading Company” traveling on the ship Sabina out of Greenport, Long Island to California for fifteen months from February 1849 to May 1850. He luckily survived that unsuccessful adventure. He was ill on the trip and lost his investment, but he did not lose his life like so many of the other crew members, including many Southampton neighbors. [Captain Henry Green’s logbook of the Sabina voyage is available on the Mystic Seaport Museum website: mysticseaport.org.] Afterwards he remained active in whaling but only locally, protecting Southampton’s shores from the savage beasts whales were considered to be at the time. Unfortunately, on one such occasion the whale smashed his boat, throwing Rogers and his crew overboard. Rogers was severely injured, resulting in an amputated limb and death by lock jaw not long afterwards. He was only able to enjoy the mansion representing his many successes as a sea captain for twelve years. His wife and three children survived him.

Capt. Albert Rogers (1807-1854)

(m. abt. 1828) Mary Halsey (abt. 1807-1835)

(m. 1837) Cordelia Halsey (abt. 1809-1887)

Mary Halsey Rogers (1839-1919)

Jetur Rose Rogers (1841-1919)

Edwin Herrick Rogers (1843-1926)

In 1843, Capt. Rogers commissioned the home’s impressive Greek Revival “mansion” volume. It is timber-framed with notches for framing members and pegged, mortise and tenon, and banded scarf joint connections. This volume may have been a conversion of the original Rogers homestead rather than a total structural replacement, with such conversions of antiquated plans into the more popular center hall style a common practice in the 1800s. The overall plan layout remains the same, but the center chimney is replaced with a center hall and twin symmetrical internal north and south end chimneys. While there is not sufficient information to prove this theory beyond a doubt, there is evidence (i.e. early framing visible at the basement and attic levels, some with roman numeral carvings, and vintage photos showing the Greek Revival volume resting on a field stone foundation) to substantiate it as a theory. Such a conversion would also explain where the slaves lived and why the first-floor ceilings are generally lower than most Greek Revival residences of this style. [An original entry on a saltbox home would have had a transom window above. The ceiling is set above the transom, with other interior doors smaller and lower so that there is wall space above the door before the ceiling. The same condition exists at the Rogers Mansion even to the extent that the decorative moldings are cut off by the ceilings.]

“Greek Revival was the dominant style of American domestic architecture during the interval from about 1830 to 1850…during which its popularity led it to be called the National Style….Not surprisingly, the largest surviving concentrations of Greek Revival houses are found today in those states with the largest population growth during the period from 1820 to 1860,” and New York State is at the top of that list.” [A Field Guide to American Houses, Virginia and Lee McAlester, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.]

A few other similar Greek Revival houses in Southampton today are the Abraham Topping Rose, Esq. House in Bridgehampton, the Capt. Mercator Cooper House in Southampton Village, the Nathaniel Rogers House in Bridgehampton, and the Capt. James A. Rogers house in Hayground (Water Mill). The latter two homes were built for second cousins of Capt. Albert Rogers. James A. Rogers also married Mary Rose, the sister of Abraham Topping Rose. The Nathaniel Rogers House and the Mercator Cooper House are also known to have been conversions of earlier residences rather than new constructs.

Mrs. Cordelia Rogers (abt. 1809-1887)

After Capt. Albert Rogers’ death, his wife Cordelia became the owner of the Rogers mansion and property until her death 33 years later in 1887. When her husband died, her oldest child was 15 years old, leaving a good amount of mothering and growing-up to do in the Rogers Mansion. By 1871 however, her daughter had relocated to Wisconsin with her husband, her middle son was married and living in another home in Southampton, and her youngest son had joined his sister in Wisconsin; Mrs. Rogers moved to Wisconsin to be with her family and stayed there for fifteen years until her death in 1887. During that time the Rogers Mansion appears to have been uninhabited. Boarders and servants that appeared on the 1865 census are not present on the property and the Rogers Mansion does not appear on cottage lists (renters) that began being published about 1882.

At some point during her ownership of the property, between 1873 and 1889, Cordelia sold part of the eastern half allowing for the creation of Oak Street, Walnut Street and other general real estate development. A deed search to identify when this sale took place, and to whom, was inconclusive. That sale reduced the subject Rogers parcel down to its present 1.7 acre size.

Upon her death in 1887, Cordelia Rogers left the property to her three children equally. Two years later, they sold it to Dr. John Nugent for $12,000. [Liber 322 of Deeds, conveyance page 194, dated June 14, 189, recorded September 6, 1889]

Slaves and Indentured Servants at the Rogers Mansion

Many slaves and indentured servants are known to have been owned by several members of the Rogers family. Because these individuals would have been housed somewhere within the Rogers Mansion, their lives contribute to this architectural narrative.

The Capt. Mercator Cooper House, on Windmill Lane, built about 1840. It is south facing and was either a conversion of, or replaced, an earlier Howell residence. Courtesy of Jeff Heatley.

The Abraham Topping Rose, Esq. Residence in Bridgehampton, built about 1840.

The Capt. James A. Rogers House, circa 1840, in Hayground. Courtesy of Jeff Heatley.

The Nathaniel Rogers House, circa 1840, in Bridgehampton. Courtesy of the Eric Woodward Collection.

Slaves and Indentured Servants at the Rogers Homestead

The attic space above the eastern 1780s wing of the Rogers Mansion is not, and has not been, a habitable area, and it is unlikely that there were slaves or indentured servants in the home past 1817. Therefore, the slaves and indentured servants of the Rogers Mansion either lived in the second floor of the 1780s volume, in the attic of the volume that pre-dated the 1843 Greek Revival construct, or in the cellar, the pre-1843 attic being the most plausible theory. The 1843 Greek Revival volume, today, may be constructed with timbers and floor boards from the earlier Rogers dwelling. A close examination of these materials may reveal proof of the presence of slaves in the home.

Dr. John Nugent (1859-1944)

John Nugent was born in Riverhead to Irish parents Robert (b.1820) and Ellen (Ducey, b.1825) Nugent who immigrated to America about 1851. He was raised in a household with three other siblings, two older brothers and a younger sister; his father worked as a farmer.

Dr. John Nugent Sr., from the collection of the Southampton Historical Museum.

After graduating with a medical doctorate degree from the University of Michigan in 1881, John Nugent settled in Southampton and partnered with Lemuel R. Wick (1831-1892) as a druggist. This early part of Nugent’s career was generally focused on everyday ailments and care while the major medical issues were handled by Dr. David H. Hallock, Southampton Village’s appointed physician. Lemuel Wick was a Southampton local who had spent twenty-five to thirty years in California before returning to Southampton in the late 1870s – early 1880s for the remainder of his life.

‘Wicks & Nugent’ built a drug store on the north side of Jobs Lane in January 1882 but the partnership ended in the summer of 1883, shortly before Wick would be put on trial for the illegal sale of liquor without a license. Wick continued to operate his drug company until the autumn of 1890 when he sold it to a Mr. Howell of Centre Moriches.

From 1884 to 1887 Dr. Nugent maintained an office in Captain Charles Howell’s building on Main Street (now located just behind Main Street to the east and just north of the subject property). In 1886 he married Helen Howell Fordham (1866-1955) of Southampton, a daughter of Henry A. Fordham (1836-1901). In 1887 he was appointed Southampton Town Health Officer upon the death of Dr. Hallock. For the two years between 1887 (the year after he was married) until the year he bought the subject property, Dr. Nugent kept an office at his father-in-law’s home on the southeast corner of Culver Street and First Neck Lane. During that time, he and his wife started a family with their first son, John H. Nugent, born in 1888. After buying the subject property, Dr. and Mrs. Nugent had two more children, both sons, in 1893 and 1897.

Once Dr. Nugent became the Town’s official health officer, his practice handled all varieties of cases, but while he was capable of addressing any size ailment or malady, he appears to have been mostly involved with major medical events and was most often referred to, for the remainder of his life, as a coroner rather than a general physician. He mended cuts to appendages made from axes, he removed bullets, he dressed wounds made from animals, he attended broken bones, he pronounced victims dead or alive, and dictated how corpses should be disposed of if unclaimed within a certain time-period.

In addition to serving as the Southampton Health Officer for thirty years and County Coroner for eighteen years, Dr. Nugent was also one of the first board members at Southampton Hospital and the first president of Southampton’s First National Bank for twenty-two years.

Assisted substantially by the realization of Capt. Albert Rogers’ Greek Revival volume, once Dr. Nugent bought the subject property, it continued to transition from a colonial homestead into a fashionable estate. Nugent also expanded the home, adding a full width front porch to the street façade complete with fluted Doric columns without bases, a common Greek Revival feature. The site plan by Atterbury and partners of 1926 indicate that the original stairs up to the porch from grade extended across its entire length. Nugent also added a second story cross gable to the east end of the 1780s volume, three second story dormers to the south side and at least one to the north side of the 1780s volume [North side shed dormer can be seen in a vintage view of the property.], made modifications to the first floor of the 1780s volume, added a bay window at the south end of the Dining Room, the bay window to the second story of the front facade, and a seven-sided bay projection to the south side of the South Parlor. With most of these expansions being along the south side, and since Dr. Nugent was a medical professional, one can’t help but wonder if the introduction of more sunlight into the home wasn’t a motivating health-related factor.

Conjectural Plans

Above: Conjectural layout of the c.1843 Capt. Albert Rogers house.

Below: Conjectural layout of the c. 1895 Dr. John Nugent house.

For at least a year before Dr. Nugent sold the subject property, he was hounded by many “New York syndicates” who were angling to possess it [The New York Times, September 10, 1899.]. He finally gave-in to the persuasive Samuel L. Parrish in the fall of 1899.

Samuel L. Parrish (1849-1932)

Samuel Longstreth Parrish purchased the subject property from Dr. and Mrs. John Nugent in October 1899 for $19,000. [Liber 486 of deeds, conveyance page 291, dated October 28, 1899, recorded November 11, 1899.] Parrish is an important historical figure in the Village of Southampton due to having been a critical participant in so many endeavors and organizations that shaped the identity of the Village during the early 1900s.

Samuel Longstreth Parrish, 1913, by William T. Smedley. Courtesy of the Parrish Art Museum.

Samuel L. Parrish was born in 1849 in Philadelphia, a city which was the largest of the colonial cities and the nation’s first capital. He was the youngest of seven children in a prominent Quaker family and was educated at Phillips Exeter Academy and Harvard University graduating with a law degree in 1870. In 1877 he established a law practice in New York City.

Samuel L. Parrish’s family included several men who made important contributions within their Philadelphia communities, such as “John Parrish (1728/29-1807), who was a Quaker minister active in promoting good relations with the Indians, and his nephew Dr. Joseph Parrish (1779- 1840), a noted Philadelphia physician who was an outspoken abolitionist and crusader for penal reform.” Also, one of Dr. Joseph’s sons, Dillwyn Parrish (1809-1886), was a prominent Philadelphia pharmacist as well as “a dedicated abolitionist and crusader for racial equality…” [Historical Society of Pennsylvania.] Samuel’s father and grandfather were noted medical physicians and his mother’s side (Redwoods and Longstreths) also included several relatives of prominence within the Philadelphia Quaker community. It is interesting that after growing up in a house across the street from the cemetery where Benjamin Franklin is buried, and in a vicinity where William Penn is known to have spent time, that Samuel L. Parrish would choose to leave a society where his family was so well- known and highly regarded. His father died when he was three years old, however, which led his mother to take him and his siblings to live on a farm the family called Oxmead in Burlington, New Jersey, in a cottage built for them by his uncle, George Dillwyn Parrish. This gave Samuel his taste for country life which he later recounted in his published reminences:

“Around Oxmead cling all the memories of our childhood connected with life in the country. When we first went to live in the cottage, Miers was about six months old and I was a little over four years of age. I remember distinctly the pleasure of being in the country, and sitting in the middle of the sandy and almost untraveled road, and allowing the sand almost by the hour to run through my fingers. We lived in this cottage for seven summers, and as children enjoyed the pleasures of the country and had the benefits of that kind of education that can be obtained only by living in the country in a simple and natural way.”

His later exposure to certain social and professional circles in New York City, and the extension of the Long Island Railroad to Southampton in 1870, must also have contributed significantly to his eventual arrival to the fashionable summer resort area Southampton Village had become by the time he began buying local property in the late 1880s.

Parrish became completely immersed in Southampton’s summer colony – amazingly - as a summer resident and weekend visitor only, not a full-time resident (he did not retire from his law practice until 1897). As a golf lover, Parrish was one of the founders of the Shinnecock Hills Golf Club in 1891. He served as the Southampton Village President (mayor) for one year and was also on the Southampton Republican Committee for over twenty years. He served as a vice president and a member of the finance committee for the Southampton Village Improvement Association, helped to establish the Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art in 1892 led by William Merritt Chase, and commissioned the construction of the Parrish Art Museum in 1897 to house his personal Italian Renaissance collection of paintings and sculpture. The Rogers Memorial Library (unrelated Rogers family) and the Southampton Hospital were both established with his help, and he and his brother, James Cresson Parrish (1840-1926), commissioned the Memorial Hall at the Southampton Hospital to remember the many area residents who served in and/or lost their lives in the first World War.

Samuel remained a bachelor until the age of seventy-nine when he married Clara Davies Bloxsom, an English born merchant’s widow, in 1928. Sadly, Parrish passed away from injuries sustained from being hit by a car in New York City at the age of 82, just four years after marrying Bloxsom, and just a few months before his 83rd birthday. His name will not easily be forgotten in Southampton.

Prior to purchasing the Rogers Mansion, in 1889 Parrish hired the well-known and talented architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White to design a summer home for his mother, Sarah Redwood Parrish, in Southampton Village named White Fences on First Neck Lane. [It is written in The Houses of McKim, Mead & White (White, 1998) that in 1887 McKim and Parrish boarded at the Rogers Mansion during one of their visits to Southampton. The names of McKim and White are also frequently interchanged. There is no record of the Rogers Mansion being a boarding house or used as a summer rental in 1887, but it is not totally impossible as the house was virtually vacant at that time, owned but not occupied by the Nugent family.] In 1891 he commissioned the same firm to build the clubhouse for the Shinnecock Golf Club, and in 1892 he commissioned them again to build a summer residence and studio for William Merritt Chase in Shinnecock Hills.

In 1897, Parrish hired architect and Shinnecock Hills Summer School of Art student, Grosvenor Atterbury, who had apprenticed with McKim, Mead & White, to design Parrish’s art museum. He hired him again in 1926 to design the commercial buildings along Main Street that involved the relocation of the Rogers Mansion 100 feet back from the street. [Atterbury’s name is on the site plan drawing, in the collection of the Southampton Historical Museum.] Parrish’s association with these two nationally recognized and accomplished architects is important in evaluating the evolution of the Rogers Mansion during his ownership. Equally important is the acknowledgment of his association with several notable sculptors including Augustus St.

Gaudens, Hermon Atkins MacNeil (and his wife Carol L. Brooks MacNeil), and the Pugi Brothers (Fratelli G. and F. Pugi) of Florence, Italy.

Soon after purchasing the Rogers Mansion, Parrish had several additions built and made many interior changes also. Although he was a single man with his main residence and office in Manhattan as well as an office in his museum across the street, Parrish must have rationalized the mansion’s expansion due to having many family visitors and hosting distinguished guests related to the art and theatre events he often arranged at his Museum and Memorial Hall. He enlarged the Rogers Mansion by adding a large one-story music room to the south side of the Greek Revival volume accessible through the south parlor; and three additions to the north elevation: a partial expansion of the northeast corner of the north parlor including a north entrance/exit; a large two-story addition including a billiard room on the first floor and an additional bedroom on the second floor; and a small two-story addition with a powder room on the first floor and the enlargement of a bedroom on the second floor. His specific changes to the interior, including the possible work of Grosvenor Atterbury, McKim, Mead & White, and one of his sculptor acquaintances are detailed later in this report.

Incorporated Village of Southampton Property Ownership 1943 – Present (Southampton Colonial Society/Southampton Historical Museum Stewardship 1952 – present)

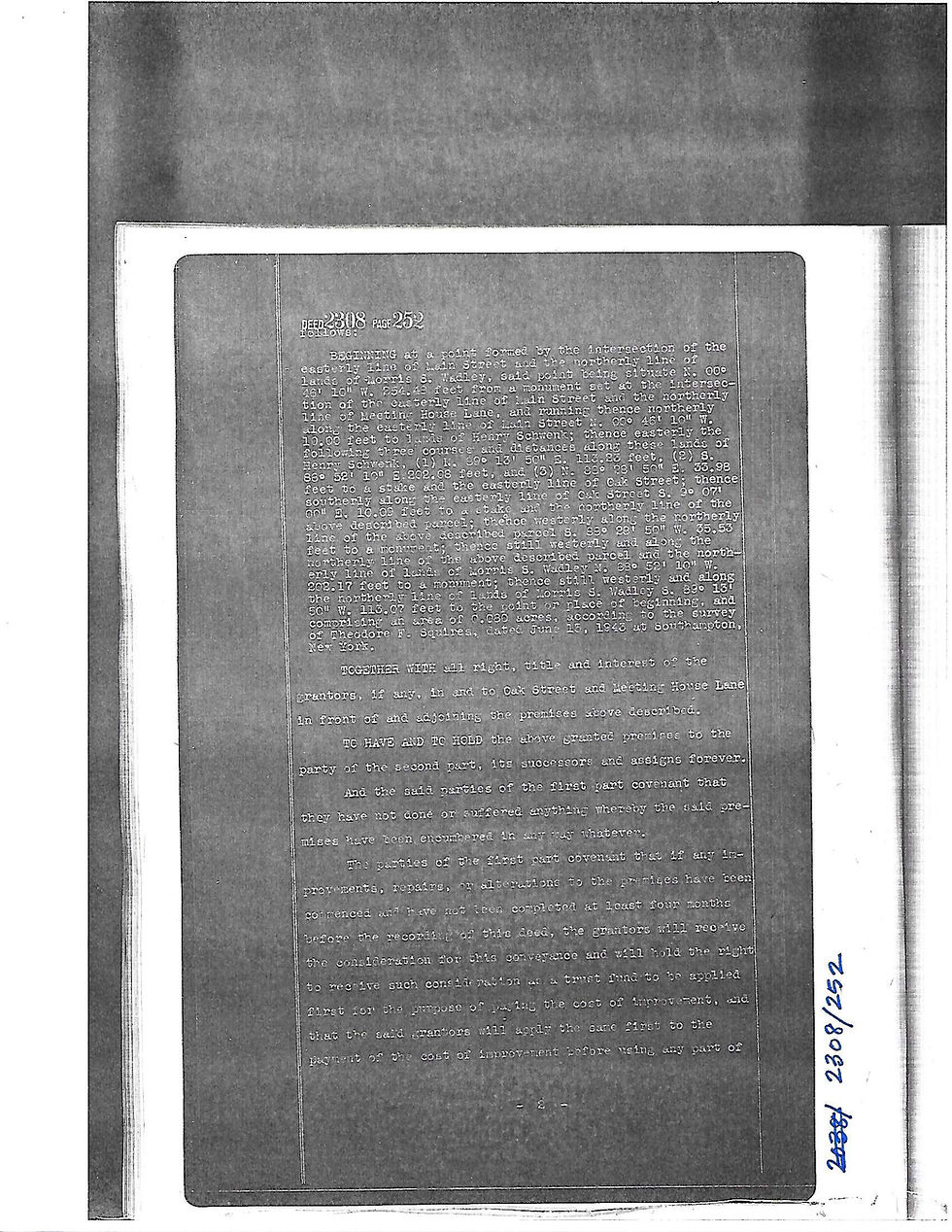

Samuel L. Parrish and his heirs owned the Rogers Mansion from 1899 to 1943, eleven years after Parrish’s death in 1932. The Village of Southampton purchased the Rogers Mansion in 1943 from the trustees of Samuel L. Parrish’s estate (Dr. Charles Carroll Lee (brother-in-law) and Frank P. Hoffman) for $4,000. [Liber 2308 of Deeds, conveyance page 251, dated June 24, 1943, recorded September 3, 1943.] In 1952 the Southampton Colonial Society (also known as the Southampton Historical Museum) began leasing the house and grounds from the Village and continues to do so at present. The thriving activities of the Museum and their careful stewardship of the building have contributed significantly to its ongoing relevance within Southampton’s daily life and cultural activities, to its continued survival, and overall good condition.

EXTERIOR DESCRIPTION

West Elevation (Front)

The 1843 Greek Revival volume is two-and-a-half stories tall, five bays wide (40.5 feet) and two bays deep (32.5 feet) with its front façade facing the street (west).

The main entrance includes a narrow line of transom and sidelights and is immediately surrounded by flat casing with double boxed corner blocks (that repeat on the interior) which are then flanked by fluted Doric pilasters. The original entry door had eight panels and has been modified to have glazing in place of the original top four panels.

White painted clapboard clads the exterior. Windows are double-hung units with six-over-six divided light patterns paired with dark green painted louvered shutters symmetrically arranged between two-story fluted Ionic pilasters that carry a cornice line of four bands of trim. (Some windows have been replaced, others removed, and many shutters have been removed.) The clearstory is symmetrically divided into five bays by pilasters with Greek key motifs. In the center of each bay are six light windows that replaced original single panel green louvered shutters and are cased with thickly three-reeded Doric pilasters. The roof edge is decorated with a heavy turned balustrade whose members were originally hole but have been replaced with half, front-facing profiles. Five equal sections face the front and rear; three equal sections face the north and south sides.

An original entry porch would have likely preceded the present full width entry porch introduced during Nugent’s ownership along with the second-floor bay window. The present entry porch is one story tall with a flat roof supported by four fluted Doric columns without bases in keeping with the 1843 volume’s Greek Revival features. The building now rests on a partial full basement of concrete and brick but originally rested on a stone foundation with partial cellar. Two brick chimneys bookend the north and south sides and are now painted white.

South Elevation (Side)

The south elevation of the 1843 Greek Revival volume is two-and-a-half stories tall and two bays wide (32.5 feet). This elevation originally had three double-hung windows with six-over-six divided light patterns symmetrically arranged about the fireplace on each floor level, with three single-panel louvered shutters aligned above them, and was later altered by the introduction of the seven-sided bay window, the Music Room and its chimney.

Extending to the rear/east of the 1843 volume is a one-and-a-half story gabled volume measuring approximately thirty-nine feet long and twenty feet deep built in the late 1780s. It is clad with shingle siding with tall exposures on its south and east sides. None of the present first floor windows are original to the 1843 or 1780 volumes. Three late Victorian south-facing shed dormers with two-over-two double-hung windows are symmetrically positioned on the south side of the gable roof and were added during Nugent’s ownership. Filling in the southeast corner between the 1843 and 1780 volumes are a one-story addition with shed roof and a two-story addition with flat roof added during Parrish’s ownership of the property. The Nugent dormers are clad with shingle siding with four-inch exposures while the Parrish additions have painted clapboard siding. The south facing second-story window of Parrish’s addition may contain a double-hung window relocated from the 1843 volume.

East Elevation (Rear)

The gable end of the 1780s volume is the dominant form against an otherwise disorganized rear elevation. On the first story is a small window with eight lights in a diamond pattern that is likely a Grosvenor Atterbury signature of sorts. On the second-story are two double-hung windows in the center of the gable end with twelve-over-twelve divided light patterns in keeping with the 1780s date of this volume.

Projecting east from the 1780s volume is an eleven-foot by sixteen-foot one-story gabled barn that was adjoined to the residence prior to 1894. It is clad with vertical board siding and presently contains four transom windows with three lights each and one vertical board door with iron hardware. Two former barn windows are now sealed. Its original use appears related to farm animals. The rear entry porch may appear to date to the Victorian period but may have actually been introduced by the Colonial Society since the primary entrance into the rear of the building is documented to have been through the barn.

Projecting north from the 1780s volume is a one-and-a-half story cross gable in-line with the east end of the 1780 gable.

North Elevation (Side)

The north elevation of the 1843 volume remains mostly intact except for the replacement of the westernmost first story window and the additions made during Parrish’s ownership. Among those are a small one-story vestibule with flat roof clad with Doric style round pilasters and enclosed with six double-hung windows with twelve-over-one divided light patterns (two of which were later covered by the Parrish addition discussed next) and one door with the same glazed patterning; and a large two-story addition with flat roof, clapboard siding, and two-story pilasters at the corners with Greek key motif. This fifteen-foot by twenty-two-foot addition has twelve-over-one glazing at the first story and six-over-six double-hung windows on the second story and is situated between the 1843 and 1780 volumes. The two-story addition also has a northern projecting one-story vestibule with clapboard siding, twelve-over-one glazing, a flat roof, and corner boards.

Another addition expands a bedroom on the second floor of the 1780s wing to the north and rests half on the powder room addition on the first floor and half on a round Doric style column. It has a flat roof, is clad with painted cedar shingle siding, and has three double-hung windows with six-over-six divided light patterns. Rather than adjoining the two-story addition to the immediate west, a small space between the two addition is left so that a bathroom can have a window for fresh air and light.

The north face of the cross gable added during Nugent’s ownership has two double-hung windows with six-over-six divided light patterns in the gable end. The first story of the 1780s volume has two small double-hung windows with six-over-six divided light patterns, a non- original door with a nine-light upper glaze panel that appears to have replaced an earlier door in the same location, and a large late Victorian double-hung window with two-over-two divided light pattern. The two handicapped accessible ramps are Colonial Society introductions.

Cupola

The 1843 volume is surmounted with a shingle-clad cupola measuring about nine-and-a-half feet square with flat Doric pilasters at the corners. The north facing door’s exterior paneling matches that of the first-floor entry door. A double-hung window with six-over-six divided light pattern is placed on each of the other three elevations. Each window is cased with very simple flat side pilasters that die into plinth blocks at the bottom and are capped with a flat cap with rounded edges and topped with a shallow flat pedimented crown molding. The Doric pilasters support a four-band entablature matching the residence. After a short flat frieze, the surviving cornice, with its original dentil molding now removed, is topped with a shallow metal roof.

INTERIOR ANALYSIS

The following is an analysis of the interior architecture (not including furnishings, paint, or wall paper) of each room in the Rogers Mansion as it existed during the compilation of this report.

General:

Floors: Until the early 1900s, wood floors were either unfinished, painted, or covered with some type of cloth (including linoleum which was invented in 1863). In the best rooms of the house, the floors would be completely covered (wall to wall except at hearths) with some type of cloth (carpet) or paint or both (which could sometimes result in a lower quality wood and/or wood floor installation). In 1881 Clarence Cook’s opinion expressed in The House Beautiful established finished wood floors as fashionable and better for one’s health rendering carpets as secondary decorative features (area rugs) rather than wall-to-wall necessities or preferences.

The earliest wood floor boards were wide and butted together. Then ship-lapped boards overcame the annoying gaps between boards as they grew and shrank with seasonal humidity levels and allowed small objects to pass through them. Ship-lapped boards are evident throughout the Rogers Mansion. The Industrial Revolution later provided tongue and groove floor boards which is the type of wood flooring most prevalent throughout the Rogers Mansion.

Doors: There are many styles of doors throughout the Rogers Mansion that are of several different ages, from early board doors with iron latches, to Greek Revival panel doors with rim locksets, to Colonial Revival doors with recessed locks. Many have been replaced outright and others reused, either in the same location or a different location, sometimes even cut to fit or turned upside-down. For these reasons one can’t be certain that any door, other than the main entry door and the door from the Cupola to the roof are original to their location.

BASEMENT

The basement is not original but was created when the Rogers Mansion was relocated. A full basement is below the 1843 volume, the western third of the 1780s volume, and all of the early 1900s two-story northern addition. The other areas have a crawl space The poured concrete foundation base is topped with a brick wall about four feet tall. A small center portion of the basement is sunken, a typical preventative measure in case of boiler failure.

FIRST FLOOR

Entry Hall:

Floor: Three-inch wide wood flooring running east-west. No pattern. Not original. The subflooring, visible from the basement level runs east-west. The original floor may possibly survive between the current finish flooring and subflooring.

Moldings: The base moldings are original to the 1843 volume. They consist of a typical Greek Revival base molding topped with an elaborate base cap well-suited to the entry hall. (The base caps are slightly different in the hall than in the two parlors.) The chair rails are original to the 1843 volume. The small crown moldings are original to the 1843 volume.

Door moldings: Not original. They are very Greek in character but were likely modifications made during Parrish’s ownership and could have been done or influenced by Grosvenor Atterbury or McKim, Mead & White (both of whom used classical faces in corner blocks and other architectural moldings [Specifically, see the Ernesto G. and Edith S. Fabbri House (New York) library by Grosvenor Atterbury with classical figures as part of the mantel and balustrade designs as well as the applied pointed diamond panel moldings on the pilaster bases; and the Joseph Pulitzer House (New York) salon and breakfast rooms with classical figures within both mantel designs by McKim, Mead & White.]) or the number of significant sculptors with which Parrish was acquainted. They are demonstrative of Parrish’s love of Italian Renaissance art and architecture. The top and side casings have applied flat gothic arch panels that die into the plinth bases also with applied flat panels. The original 1843 moldings would have been more carefully aligned with the base moldings. The corner blocks, without the classical visage, may be original (they are present in rectangular shape on the exterior of the main entrance surround), but the casings were probably more like the chair rails and died into plain plinth blocks. The pediment tops may also be original and mimic those on the exterior of the cupola.

Entry Door: The original eight panel Greek Revival door was modified during Parrish’s ownership so that the top four panels became one glazed panel. The transom and sidelights are original to the 1843 volume with orthogonal divided muntin patterns.

Closet Door: Single panel with Greek Revival panel moldings and casing. The door handle is not original. It is interesting to observe the transition of moldings on the left and right side of this door.

Hardware: Not original. Greek Revival hardware would have been rim lockset boxes applied to the face of the door (not inset) with porcelain handles and skeleton key holes.

Stair: Original Greek Revival stair including turned newel post, simple round tapered balusters and continuous handrails all a dark brown natural or painted finish. Decorative bracketing that is painted white along the outsides of the treads is more complex than other similar Greek Revival residences and a character defining feature of the residence.

North Parlor: (Hall) The North Parlor was originally larger than it is presently, probably one room spanning the entire east-west dimension of the 1843 volume and evidenced by a wood floor border that survives in the Dining Room closet.

Floor: Original two-inch wide wood flooring running north-south with a five-strip-wide border outline. Inside the border would have been a floor cloth, remnants of which are now believed to be in the Butler’s Pantry. Floor cloths originated in the mid-1700s in England. Their designs mimicked carpets, tile and wood parquet common in the great estates of the period. Eventually, however, they were considered quite convenient because they were more durable than carpets, easier to keep clean, warmer in the winter and bug resistant in the summer. They were made locally but the higher quality cloths were imported. While they were less expensive than carpet, they were not inexpensive due to being labor intensive and requiring long drying times.

The floor cloth in the Entry Hall of Melrose House, a Greek Revival style mansion completed in 1845 in Natchez, Mississippi.

“Nathan Hawley and Family,” Albany, N.Y., signed William Wilkie, 1801. Albany Institute of History and Art. (From Floor Coverings in New England Before 1850).

A flooring advertisement published in The Corrector, April 25, 1838.

Entry Hall

Stair Molding Study

Left to right: Entry Hall at the Rogers Mansion; Cupola at the Rogers Mansion; Fragments of remailing stair moldings at the Nathaniel Rogers House, Bridgehampton; Stair Detail at Sarah Redwood Parrish’s House by McKIm, Mead & White, Southampton Village; 1829 Dayton House, East Hampton; Capt. James A. Rogers House, Hayground;.First Presbyterian Church of Southampton, 1843.

Door & Trim Study— Nathaniel Rogers House

Left to right: A Parlor on the first floor: notice the door style and hardware, the door trim, the height of the room, the crown molding at the ceiling, and the fireplace surround and hearth material; A bedroom facing the street on the second floor: notice the window trim with single panel below, the base molding, the crown molding, and the height of the room; detail of first floor window trim, base molding, and panel molding; another view of a second floor door, door hardware, and door trim (with plinth block).

Door & Trim Study—Capt. James A. Rogers

Left to right: Trim between southwest and northwest parlors on first floor; Main entry door paneling and hardware in background—entry hall door paneling and hardware in foreground; Door and ceiling trim at main entrance; typical first floor door trim and corner block.

Moldings: The base moldings are original to the 1843 volume. Some of the small crown moldings may survive from the original 1843 volume. The Dining Room closet indicates that the Greek Revival chair rail would also have originally existed in the North Parlor.

Door/window moldings: Not original. (See Entry Hall) The corner blocks are blank; the sides and tops of the casing have applied panel moldings that end in a diamond point at the top and die into plinth bases (with recessed panels) below. There is no bead and reel trim below the crown molding (like in the Entry Hall) and the pointed pediment tops are shorter than in the Entry Hall, disappearing completely at the three westernmost windows whose crown moldings meet the crown molding at the ceiling. Each window has a double panel below (except those at the north exit vestibule) which was a Parrish modification (see original single Greek Revival panels on the second floor).

Interior Door: The single door between the Entry Hall and North Parlor is original to the 1843 volume. It has stile and rail construction and six panels, with applied moldings on the hall side and flat panels on the parlor side. The hardware is not original.

North Vestibule: This area was an early Parrish addition (before 1926) and is Colonial Revival in style with fluted Doric pilasters dividing the vestibule from the parlor. A tall frieze is surmounted with dentil and egg and dart moldings before meeting a small crown. The window casings have Greek Revival profiles and die into a window sill that runs around the perimeter of the room. The “colonnade” treatment of the opening between the vestibule and the North Parlor was a popular but short-lived millwork feature during the Colonial Revival period. It occurs three times in the Rogers Mansion: at the North Parlor, the South Parlor, and in the Music Room; all Parrish embellishments.

Fireplace: The fireplace is original to the Greek Revival 1843 volume but the hearth, with small subway shape tiles, is a Parrish modification. The insert is typical to the Greek Revival period but its particular maker, “Janes & Kirtland, NY” [Adrian Janes began the company in 1844 in Manhattan and later relocated to the Bronx when it received the commission to build the dome for the United States Capital Building in the 1850s. The same firm fabricated the Bow Bridge in Central Park and supplied the iron for the Brooklyn Bridge. They also fabricated fountains, cooking ranges, furnaces and statuary.], was only just being formed as a company at the time the 1843 Greek Revival volume was being constructed leading one to conclude that it was introduced to the home later. The surround appears to be original and would have been painted plainly or to appear as marble (tromp l’oeil).

South Parlor: (Parlor) The South Parlor is currently one room spanning the entire east-west dimension of the Greek Revival volume but was probably two separate rooms originally with the fireplace centered in the western room. This theory is supported by the present number of doors into the room. A small fragment of a separating wall may exist to the east of the present French doors.

North Parlor

Fireplace Study – Greek Revival

Left to right: fireplace in the first floor of the Nathaniel Rogers House in Bridgehampton; fireplace in the second floor of the Nathaniel Rogers House in Bridgehampton; fireplace at the William Hadwen House in Nan- tucket; fireplace in a second floor bedroom at the Capt. James A. Rogers House in Hayground. (All cast iron exam- ples; three with simple surrounds, two of which are marble.)

Floor: Three-inch wide wood flooring running east-west. No pattern. Not original.

Moldings: The base moldings are original to the 1843 volume. Some of the small crown moldings may survive from the original 1843 volume.

Door/window moldings: Not original. (See Entry Hall) The corner blocks are blank; the sides and tops of the casing have applied panel moldings that end in a diamond point at the top and die into plinth bases (with recessed panels) below. There is no bead and reel trim below the crown molding (like in the Entry Hall) and the pointed pediment tops are shorter than in the Entry Hall, disappearing completely at the three westernmost windows whose crown moldings meet the crown molding at the ceiling. Each window has a double panel below (except those at the north exit vestibule) which was a Parrish modification (see original single Greek Revival panels on the second floor).

Interior Doors: The three interior doors are all different. The western hall door is Victorian with six panels and panel moldings on both sides; its hardware is Victorian. The eastern hall door is Greek Revival with six panels with panel moldings only on the hall side; its hardware is Victorian. The east door is shorter than the hall doors; it is Federal with five panels and is sealed on the Dining Room side. (It is probably like the two other five panel doors in the Dining Room. It is interesting that it wasn’t removed entirely, as if its hierarchy was nostalgic.)

Fireplace: The fireplace is original to the Greek Revival 1843 volume but the hearth and surround, with small subway shape tiles and applied moldings, are Parrish modifications. The fireplace surround, in particular, is another short-lived Colonial Revival millwork feature.

General:

Six of the nine door and window casings have the classical visage within the corner blocks, as if Parrish was implementing them one by one as he was able to acquire them rather than all at once. The three without them are all at the southeast corner.

The colonnade millwork feature spans the entire south elevation in line with the face of the fireplace and is supported by five Doric pilasters.

There would have been three south facing windows originally. The southwest window was made into a mirror when the Music Room was added; one of the two southeast windows was removed, probably when Nugent’s seven-sided bay projection was added.

The east facing window original to the Greek Revival volume was removed when Parish expanded the south end of the Dining Room. Its lower single panel survives.

Music Room: The Music Room and its brick fireplace were additions made during Parrish’s ownership before 1926 and are Colonial Revival in style. The floor finish is three-inch wide wood strips running north-south without pattern. The base, door and window moldings are simple; the crown moldings are more elaborate. The fireplace surround has engaged fluted Doric colonnettes, a frieze with sunburst pattern, and a crown molding with egg and dart molding. The colonnade dividing the Music Room from the seven-sided bay projection is supported by two fluted Ionic pilasters that support a tall frieze and crown with dentil molding. The Music Room has a skylight in the center with an iron and glass roof with a decorative pattern that is now obscured from view by screening and protective covering.

The seven-sided bay projection was an extension made to the south side of the South Parlor during Nugent’s ownership. It was then moved and added to the south end of the Music Room by Parrish. Each segment is separated by Doric pilasters that support a plain frieze above which is a simple crown molding with casing. Each window has a single panel below (in keeping with the single panels originally below the 1843 volume windows). The base molding runs uniformly around the room and base of the pilasters, and the height of the panels on the French doors is coordinated with the base and window sill moldings.

South Parlor

Dining Room: The Dining Room occupies the westernmost third of the first floor of the 1780s volume. It was first expanded by a large bay window projection along almost the entire south wall made during Nugent’s ownership. Parish later enlarged the south end of the Dining Room again removing Nugent’s bay window and filling-in the corner between the 1843 volume and Dining Room completely. The bay window framing survives at the first-floor framing level. The interior finishes of this room vary in date in response to being modified several times.

Floor: Three-inch wide wood flooring running north-south. No pattern. Not original. There is a continuous floor seam running east-west where the room was expanded to the south.

Moldings: The crown moldings are not original and are of a common profile readily available today. The door and window moldings are Greek Revival in style; most are not original. An exception is original door casing – without many years of paint layers – on the inside of the closet door. This door would have originally led one from the 1780 volume into the 1843 volume. The base moldings throughout the room are mostly Greek Revival in style; those along the west wall appear original.

Doors: The stair and closet doors are early five panel Greek Revival doors with panel moldings on both sides. Paint ghosting of an earlier bean style handle and latch can be seen on the Dining Room side face of the stair door. The French Doors and door leading to the kitchen are not original.

Mantel: The fireplace mantel is Colonial Revival in style and very similar to the mantel in the Billiard/Exhibit Room. Both fireplaces and surrounds can be attributed to Parrish’s ownership. The hearth materials are almost identical, but the brickwork is different.

Billiard/Exhibit Room and Powder Room: The Billiard – now Exhibit – Room and its fireplace were added to the Rogers Mansion at the northeast corner where the 1843 and 1780s volumes met during Parrish’s ownership before 1926. Its moldings, doors and mantel are in keeping with the Colonial Revival style of that period.

Music Room

Dining Room

Exhibit/Billiard Room

Fireplace Study – Classical Revival

Left to right: Rogers Mansion Music Room: note the engaged fluted Doric colonnettes with entasis, the egg and dart and bead and reed moldings; Rogers Mansion Exhibit/Billiard Room: note the paired Doric colonnettes with entasis and two bands of bead and reed molding above and below the frieze; Rogers Mansion Dining Room: note the paired Doric colonnettes with entasis and two bands of bead and reed molding above and below the frieze (very similar to the Exhibit/Billiard Room); Fireplace at Sarah Redwood Parrish House by McKim, Mead & White: note the paired Doric colonnettes with entasis and overall similarity with two of those at the Rogers Mansion.

Butler’s Pantry: According to the Southampton Historical Museum, the Butler’s Pantry was added in 1911 during Parrish’s ownership of the residence. However, the double-hung window with two-over-two divided light pattern is more closely aligned with Nugent. Moldings are plain or absent. The ten-light upper glass pantry doors have divisions that align with the shelves leaving the top two panes strangely smaller than the other eight panes. The Greek Revival floor cloth is relocated here from the North Parlor. The original wood flooring is below. There is a continuous north-south seam where the room was later expanded.

Kitchen: The 1780s volume was enlarged several times, probably by the Rogers family, Nugent, and Parrish. The Kitchen’s Victorian character and present appearance are largely the work of the Society. The flooring is not original. It matches the Dining Room but runs east-west and has a patched portion near the Dining Room relative to the room’s former configuration. The ceiling has wood beaded board with a natural finish. The walls have vertical beaded board wainscoting. The east facing pantry window is by Grosvenor Atterbury who used the same window style on the Parrish Art Museum. A former transom window above it can be seen from the interior.

Doors: Two board doors of unknown date enclose the mop sink closet and adjacent closet; the closet door is older; the mop sink closet is a Society creation. The window above mop sink door is sideways. It is similar to the twelve-over-twelve windows in the 1780 east facing gable end indicating that it could be reused from a former previous location within the residence.

Rear Hall: The Rear Hall has been completely modernized by the Colonial Society to include coat closets, a handicapped accessible Powder Room, a handicapped accessible entrance/exit, and a laundry closet. The rear stair is the exception. It is early and appears to have board walls and original stringers on one or both sides. It was probably relocated to its present location from elsewhere in the residence.

Storage Room/Barn: The storage room was clearly a barn originally. It rests on logs that may have helped to roll it to the house when it was originally connected. It has vertical board siding, a board door with iron hinges, locks and latches, small transom windows, and seams where larger openings formerly existed. Its framing has been concealed on the interior. The board sheathing of the east side of the residence is visible from the interior along with indications of manipulation to the right side of the non-original door to the Rear Hall. The site plan by Atterbury and his partners of 1926 indicate that there was a central exit out of the barn’s east end.

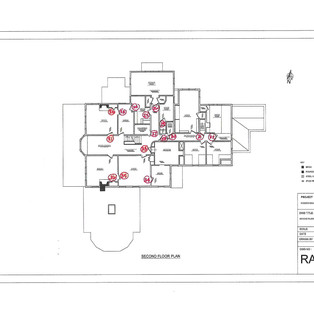

SECOND FLOOR

1843 Volume:

Stair Hall: The bay window, added during Nugent’s ownership, has neither Greek Revival nor Colonial Revival casing.

Butler’s Pantry

Kitchen & Rear Stair

1843 Volume: Stair Hall

Floor: Three-inch wide wood flooring runs east-west; not original.

Moldings: Greek Revival. The crown molding does not appear to be original.

Stair: Greek Revival.

Northwest Bedroom:

Floor: Two-inch wide wood flooring running north-south original to the 1843 volume.

Moldings: The door, window, and base moldings are original to the 1843 volume.

Doors: The Dutch door is Greek Revival in style and not original to its present location. It may have been relocated from the kitchen where Dutch doors were common. The Closet door is original to the Greek Revival volume. The door to the adjacent room is Victorian.

Mantel: Greek Revival except hearth finish which was likely added during Parrish’s ownership and matches several others in the residence.

North Middle Rooms: The easternmost room was a bathroom. The middle room may also have been a bathroom. A water heater is located above it in the Attic.

Floor: Two-inch wide wood flooring running north-south original to the 1843 volume. There is a floor seam near the door between the two smaller rooms indicating this portion of the wall to have been in an earlier location, probably between the two original northeast 1843 windows.

Moldings: The north facing window, its casings and panel molding are original to the 1843 volume.

Doors: The French door to the hall is not original.

Library:

Floor: Two-inch wide wood flooring running north-south original to the 1843 volume.

Moldings: The base moldings are not original. The window moldings are original and Greek Revival in character. The east and west door casing is Colonial Revival.

Doors: The French door at the hall is not original. The Archive door is Colonial Revival (and probably replaced an original 1843 windows). The door leading to the Southwest Bedroom is Greek Revival. The closet and doors were added by Parrish or Nugent.

Windows: The windows appear original to the Greek Revival volume but the fact that the easternmost window is without panel below seems to indicate that this room may have been formerly divided into two separate rooms.

Southwest Bedroom: This room has a call button next to the East door to the now library. This call button system is not noticed anywhere else in the residence. This room is said to have been Parrish’s bedroom.

Library

1843 Volume: Northwest Bedroom

Archive Office

Archive Storage

1843 Volume: Southwest Bedroom

Floor: Two-inch wide wood flooring running north-south original to the 1843 volume.

Moldings: The door, window, and base moldings all appear original to the 1843 volume.

Doors: The French entry door is not original. The east door to the now library and the Closet Door are Greek Revival.

Mantel: Greek Revival except hearth finish which was likely added during Parrish’s ownership and matches several others in the residence.