Southampton's 20th Century Influencers: Jane Wilson, Artist of the Ethereal

- Mary Cummings

- Nov 23, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 1, 2022

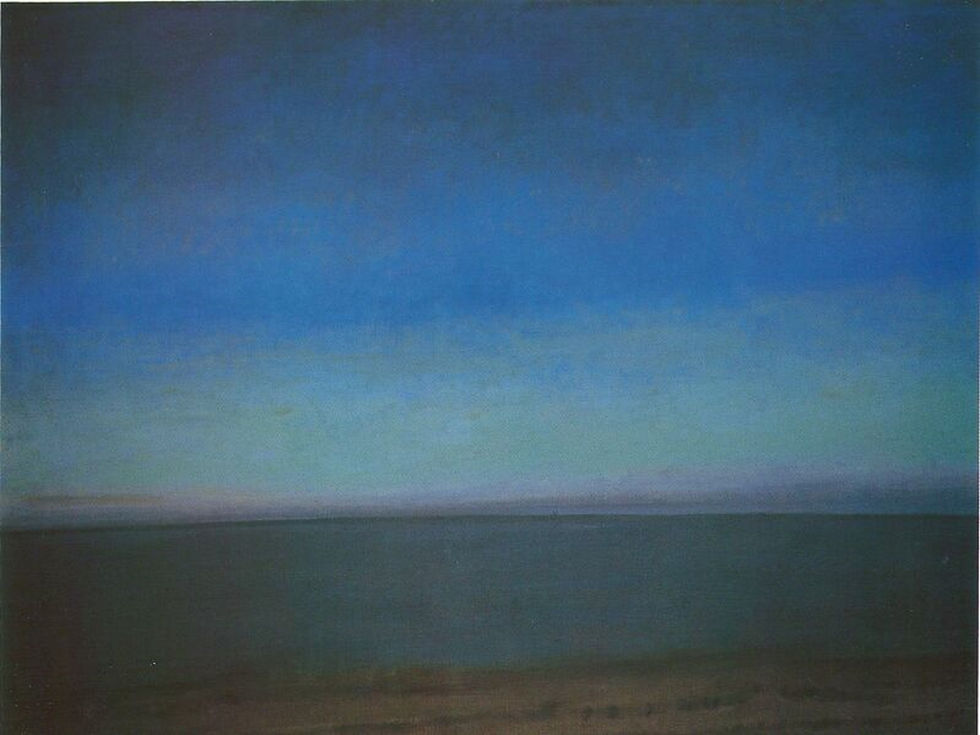

Artist Jane Wilson, best known for he luminous landscapes hovering between abstraction and representation, once told an interviewer that the challenge she faced in her work was to capture on canvas “moments of strong sensation—moments of total physical experience e of the landscape, when weather just reaches out and sucks you in.” When you think about it, she added, trying to trigger those moments “with pigments of ground-up earth—it’s really very mysterious.” In the later years of her long career as a painter Wilson focused almost uniquely on triggering those moments of transcendence, when the weather activating her vast atmospheric skies is not just seen, but palpably felt.

Born in 1924, Wilson grew up on a farm beneath the wide skies of the Iowa flatlands and spoke later of the “great weight of the sky and how it rests on the earth.” As an adult, she would gravitate to New York City when she and her husband John Jonas Gruen would be part of New York’s mind-century bohemian whirl. Then, when they bought a carriage house in Water Mill and began spending summers on eastern Long Island, the flat potato fields running right down to the sea reawakened her love of the uninterrupted landscape. And, like many another artist, she was struck by the area’s storied light.

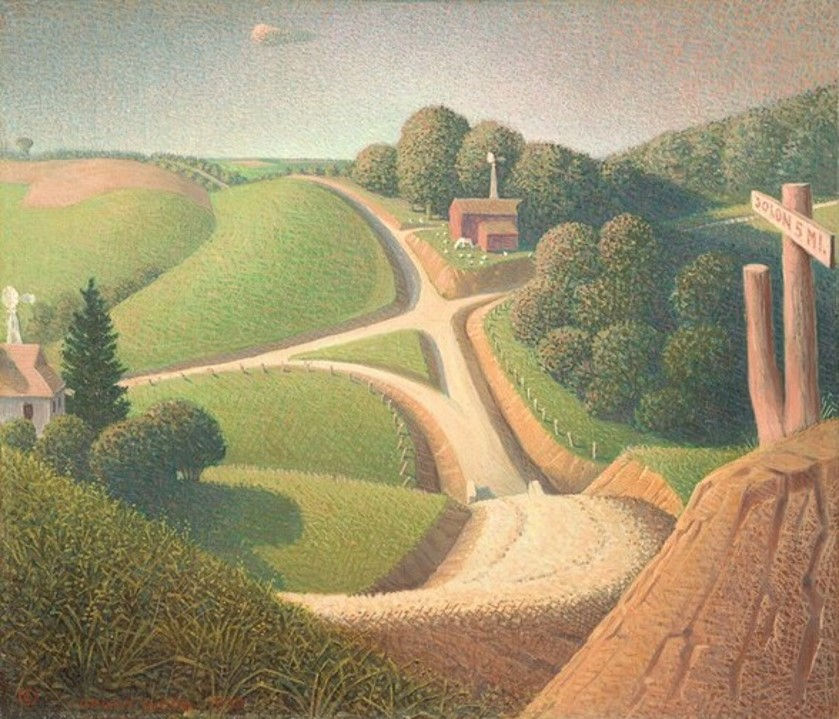

The paintings inspired by the sky, sea, land and light around Water Mill are still far in the future in 1941 when Wilson enrolls at the age of 17 at the University of Iowa to study painting and art history. The art department at the university, previously led by the 1930s allegorical regionalist painter Grant Wood, was being revolutionized to expose students to what was going on in New York, including the first glimmerings of abstract Expressionism.

Meeresstrand, 1935 by Max Beckman & Pennsylvania Landscape, 1936 by Jackson Pollock

The department head would travel to New York and bring back paintings ranging from the expressionist Max Beckmann to the upstart Jackson Pollock.

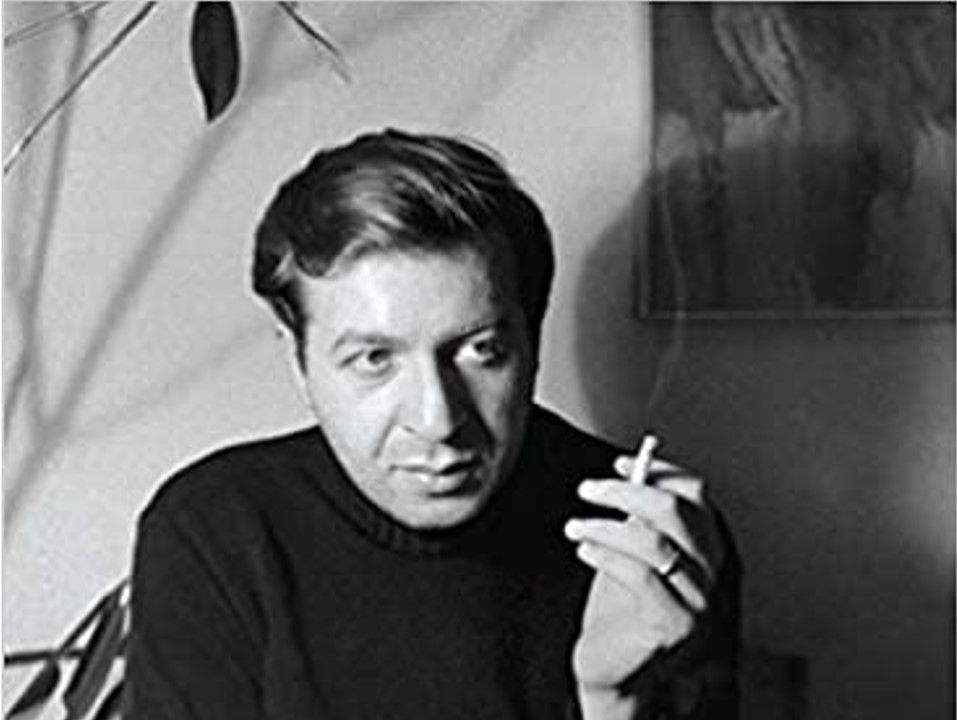

Another influence is the artist Philip Guston who is the university’s artist-in-residence from 1941 to 1945. A painter, he is also known for his drawings, murals and prints--and is, by the way, currently the subject of a major—but postponed—respective.

In the early 1940s Guston is in thrall to the early Renaissance Italian painter Piero Della Francesca and impresses Wilson with his seeming obliviousness to all but his art. “Here was this handsome hulk of a man,” she later related, “whose mind was so concentrated on his own reality that he didn’t seem so much a part of the daily world…His inner world took precedence over absolutely everything else.”

After graduating Phi Beta Kappa, Wilson remains at the university to teach art history for another two years. Then one day she is at the lectern teaching a class on oriental art when, in a life-altering moment, the exotically handsome young student who had been impatiently maneuvering to catch her eye, succeeds. John Gruen is barely 20 when he falls madly in love with the stunning 22-year-oldJane Wilson on sight. He enrolls in her class, makes himself as conspicuous as possible and, once the ice is broken, his romantic passion proves irresistible—and contagious. Tall, dark-haired and with a continental flair acquired from his cultured Jewish family and their enforced European travels staying ahead of the Nazis, Gruen is full of nervous energy and, as he later acknowledged, vague outer-directed social and cultural ambitions. “When we met,” he wrote in The Party’s Over Now, is lively and very candid memoir of the 1950s, “Jane’s inner life was far more complicated than mine.”

Up to then, Jane had seemed set on a path toward achieving her artistic goals in a fairly quiet, if determined, fashion. Growing up on a farm, as she later recalled, she had roamed its wide expanses alone, developing a deep relationship with the natural elements that would remain such a strong influence on her art. She was understandably a shy and self-involved child. When, as a young woman of 22 she is suddenly the object of John Gruen’s outsize ardor, there is never any threat to her goals as an artist, but it does mean the end of anything resembling a quiet life.

On the evening of March 28, 1948, a tiny wedding party arrives at the Oskaloosa Congregational Church to celebrate the nuptials of Jane Wilson and John Gruen. Gruen—with no patience for the advice of family and friends who are aghast at what they view as youthful impetuosity—is deliriously happy. Wilson—ravishing in a white suit trimmed with silver fox—is clearly in love but visibly anxious at taking such a consequential step at top speed. Her jitters are only magnified when John’s best man—his brother Martin—fails to appear. After waiting as long as possible, the decision is made to proceed without him and the soon-t-be husband and wife head slowly down the long aisle toward the altar. Three feet from their destination Jane slumps to the floor in a faint. Joh, horrified, is momentarily paralyzed. But when Jane’s mother rushes to her daughter’s side and pronounces the whole affair a terrible mistake, he regains his composure and shoos her and the others away.

In the end, Jane revives, insists on going ahead with the ceremony, and the inauspicious incident is never mentioned again.

There is no question where the couple will live as soon as they can extricate themselves from Iowa. Bound for glory, they head for New York City’s Greenwich Village, the only place where their lack of money and their high hopes will not be out of place in a neighborhood of free-spirited, arts-oriented bohemians. What they find when they look for an apartment is a parlor floor (one room) at 319 W 12th Street with “cooking privileges” (but no kitchen), a bathroom down the hall, a gloomy interior and a rent of $12 a week. A working fireplace is its best feature but it’s not long before John reports that the dismal décor has succumbed to Jane’s artistry. She paints the walls white, adds bunches of flowers and resumes painting producing works to hang on the walls.

319 W. 12th Street in 1940 and Today

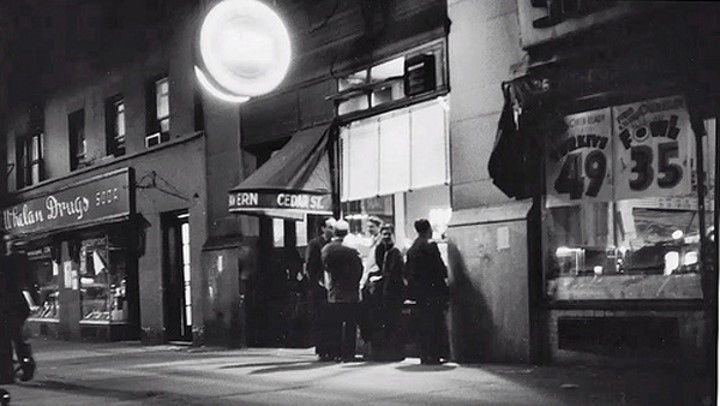

Unable to find a position with a salary that would make teaching worthwhile, Jane devotes her time to painting diligently in the tiny apartment, doing mostly figures, still lifes and imaginary landscapes. Evenings are often spent at the famous Cedar bar. Unimpressive except for its neighborhood clientele of hard-working, hard-drinking artists, the bar brings the Gruens together with some who will become lifelong friends, including artists Jane Freilicher, Larry Rivers, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan and poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery.

Watching Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning drink and talk art into the night is the bar’s main attraction and a few of the women artists pride themselves on matching the men drink-for-drink. Not Jane, who could not shed her aura of elegance if she wanted to. Reflecting later on the scene at the Cedar and her place in it, she said she had “floated around the periphery,” unwilling to participate in what she called the “scrappiness. She may not be engaged in the bar’s rowdiness but is nevertheless susceptible to the pull of Abstract Expressionism, which dominate the discourse there and is about to dominate the art world.

It’s not easy in the early fifties for young as-yet-unknown artists to find a gallery willing to show their work. At midcentury the art world is fairly small and closed. The big-name uptown galleries are giving important shows to the artists who have broken through to become heroes of Abstract Expressionism, but for the young artists experimenting downtown, it is increasingly obvious that they will have to create their own opportunities. What happens next is the dawn of a downtown art scene spearheaded by artists co-operatives. At the Cedar bar one evening Jane is approached to join one of the first to be launched, the Hansa Gallery, and she becomes a founding member.

Taking as its mission the recognition of New York’s emerging talent, the Hansa opens on East 12th Street with a roster that also includes Helen Frankenthaler, Larry Rivers, Jane Freilicher and Fairfield Porter, among others. Jane has the first of her three solo exhibitions at the Hansa in 1953 with encouraging results. The show is reviewed in the Times and the Tribune, she sells two paintings, and goes on to have two more shows at the Hansa before leaving the gallery in 1958, a year before it disbands.

As Jane’s career begins to take off, she and John are also very much part of the social excitement whirling around their growing cohort of young painters and poets. Reflecting on those frenzied times, John Gruen wrote that he and Jane “ran around like crazy. We were everywhere.” At the Cedar, the two Janes often gravitate together.

Around the time when Larry Rivers buys a modest house in Southampton in 1953, Jane and John, along with others among their downtown friends, discover the joys of escaping the city to spend summers on eastern Long Island.

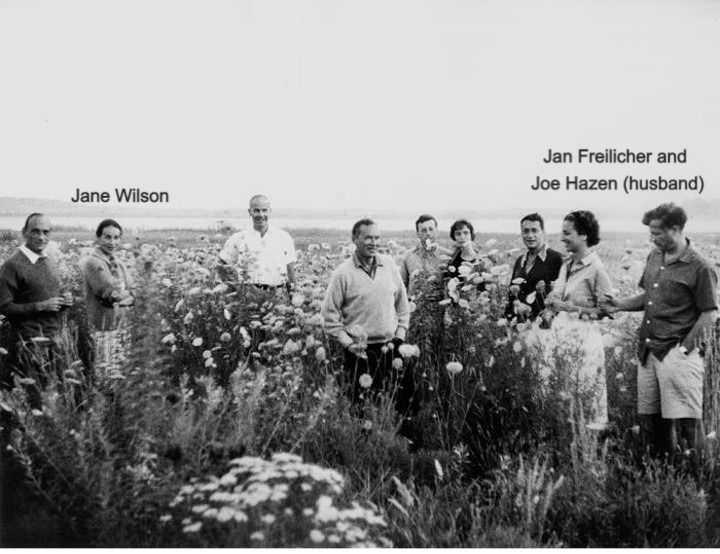

For Jane, the flat farm fields and low horizons, reminiscent of the Iowa farmland of her childhood, have a special appeal. For several successive years she and John share a house with Jane Freilicher—now one of Jane Wilson’s closest friends—and Freilicher’s husband Joe Hazen.

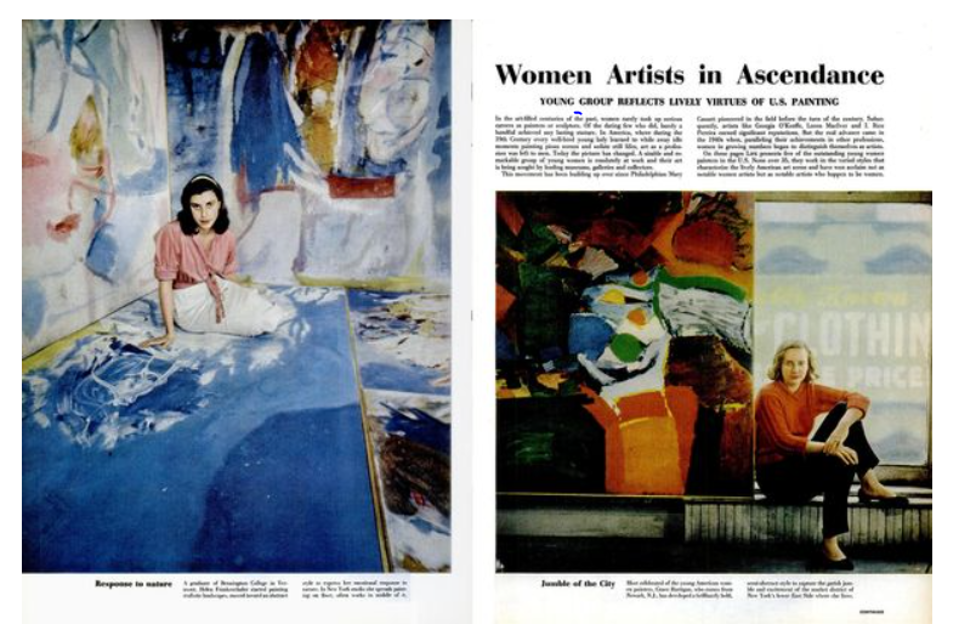

Mingling with her abstract expressionist contemporaries at the Cedar bar and elsewhere, Jane, too, is experimenting in that mode. She will be featured in a 1957 issue of LIFE magazine, along with Joan Mitchell, Nell Blaine and Helen Frankenthaler in an article titled “women Artists in Ascendance.” It’s considered a groundbreaking article, for which she is photographed in her New York studio.

By that time, Jane has already been turning away from pure abstraction. Asked later about the shift, she recalled that “One day in the 50s I just woke up one morning thinking about painting and everybody is painting wildly abstractly and being very serious and macho, and I thought, ‘Oh, I really like subject matter.’” Fairfield Porter—older, more established and committed to modernist representational painting—becomes especially important to her, encouraging and validating her surrender to the powerful urge to put subject matter back in her paintings.

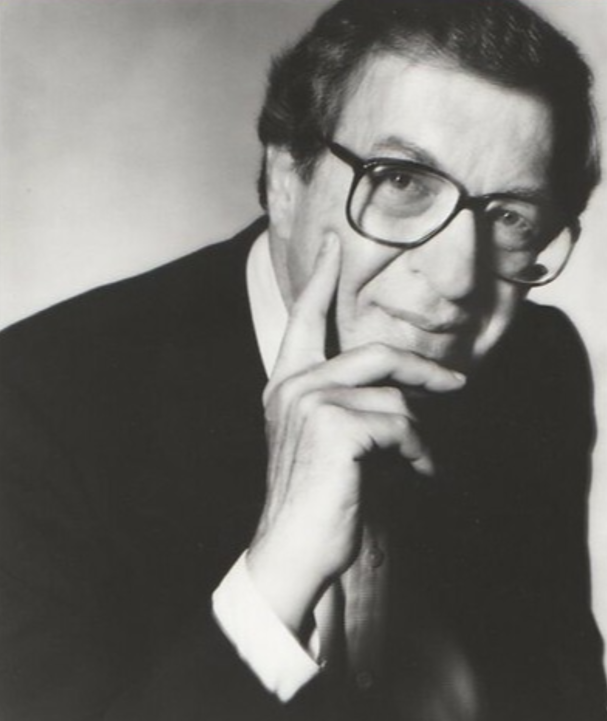

Eventually, John will find his groove as a music and art critic for the Herald Tribune and will be in high demand as a writer about cultural topics for other prestigious publications. But in the first years of their marriage he is composing art songs, a notoriously unprofitable enterprise, and struggling to find work suited to his wide cultural interests.

From the mid-fifties to the mid-sixties landscape and cityscape paintings dominate Jane’s output. Of this period she said later: “In 1956, I found myself in one of those lucid moments that occurs every 20 years and I realized I wasn’t a second generation Abstract Expressionist. I looked at the ingredients of what I was painting and felt an uncontrollable allegiance to subject matter, and to landscape in particular.” Having left 12th Street, with its bare-bone amenities behind by this time, the Gruens are living on East 10th Street across from Tompkins Square.

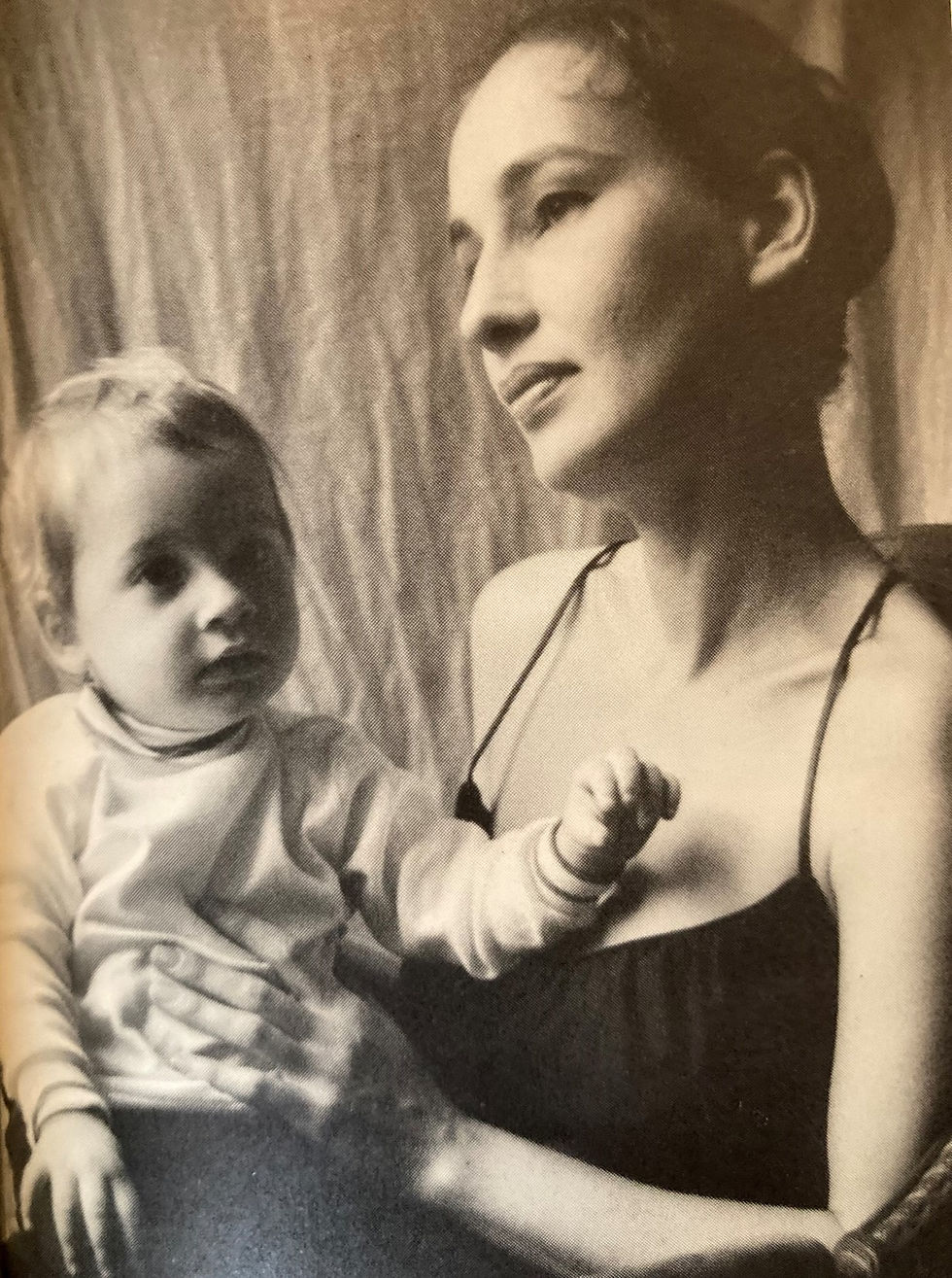

They also become parents with the birth of their daughter Julia in 1958, a joy that carries new responsibilities.

Jane and John in Harper's Bazaar, 1965

Jane accepts remunerative work as a fashion model to support the family and her career as an artist. Though she seems to take this distraction from her work in stride, she is certainly aware of the prevailing attitude in the art world, which disdains fashion and believes that anyone willing to take a paycheck, especially for work in such a shallow environment, could not be a serious artist.

Nor is she unaware of the macho bias against marriage in fifties art circles. Reflecting later on the ways in which she was a bit of a misfit at the Cedar bar, she recalled that “the most vocal of the women painters tended not to be married…There was a position taken, she said, that you could not be married and be a painter—it indicated you were not serious.”

Whether on a lark or with hopes of giving their budget a boost, Jane spends seven frantic weeks in 1957 as a contestant on one of the most famous and ill-fated quiz shows of the Fifties, The $64,000 Challenge. One of her co-contestants is her friend Larry Rivers. In the end, Jane is not a big winner. For her seven mad weeks she receives a $1,000 consolation prize, countless cartons of Kent cigarettes, and a blast of public exposure that might boost the budge indirectly if it helps sell more paintings. Rivers, on the other hand, wins $32,000. When the scandal hits and the show is revealed to have manipulated the performances of some of its contestants, rivers admits to having been slipped an envelope with the questions beforehand, but claims to have resisted any temptation to look inside.

The decade of the Sixties opens for Jane with decisive events in both her professional and personal lives. In 1960, The Museum of Modern Art acquires her painting “the Open Scene.”

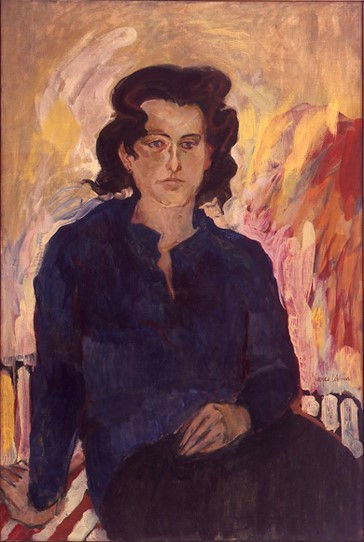

Also in 1960, Andy Warhol commissions her to paint his portrait, which she calls “Andy and Lilacs.” And soon she is asked to join New York’s primary showcase for the younger generation of artists, the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. There she is among friends, including Jane Freilicher, Grace Hartigan, Larry Rivers and Fairfield Porter. With its purchase of “the Open Scene,” MoMa has not only signaled that Jane has become an important force in American painting, it pays her a handsome sum.

Unexpectedly flush, the Gruens are almost immediately put in the path of temptation when they spy a beautiful 1920s carriage house in Water Mill with a “For Sale” sign. It is—once again—love at first sight. Though Jane—never as impulsive as her husband—might have hesitated to turn their bundle over so soon to a real estate agent, she allows herself—once again—to be swept along by the force of John’s ardor. And she will never have a moment’s regret.

Their Water Mill home will become a vibrant gathering place for the Gruens’ many friends who will come to party, to refresh themselves at the beach, to make mischief, and to spend long summer evenings talking, drinking and feasting on seafood and corn on the cob.

A glimpse of Jane’s Water Mill studio

The gang gathers in Water Mill

Most important for Jane the artist are the land, air, sea and sky of Water Mill, which will provide lifelong inspiration as she continues to evolve as a painter. “There is a kind of light there,” she tells interviewer Mimi Thompson in 1991, “that occurs when you’ve got water on both sides.”

To capture its special effect she’s using a technique of layering wet paint on dry. Curator Klaus Kertess, in an essay accompanying a 1996 exhibition of Jane’s paintings at Southampton’s Parrish Art Museum, credits her patient building of sometimes as many as 30 layers of wet and dry with achieving the diffused, mysterious light recognizable in the later paintings she is best known for.

In the preface to his book “the Sixties: Young in the Hamptons,” John Gruen lists the friends who form the nucleus of the group most often gathered as their guests in Water Mill. Several couples are on the list, including Jane Freilicher and her husband Joseph Hazen, poet Kenneth and Janice Koch, Anne and Fairfield Porter, and Larry and Clarice Rivers. When, in 1960, Rivers hires the Welsh-born Clarice to take care of his children, the artist, who loves to shock with his unconventional antics, finds a match in his free-spirited nanny, and the Water Mill nucleus gets a lively new member. (Clarice is second row, second from left in the photo.) Of course, as Gruen acknowledges in the Preface to his book, “along with some genuine good times and harmless merry-making, there could also be too much drinking, lots of pot-smoking, some casual sex and on occasion some very real and quite ugly nastiness.”

Always following her own path, resisting the trend of the moment, Jane moves at her own pace to arrive at the moody landscapes with their big skies, low horizons and palpable weather. To explain her unrushed approach, she tells Mimi Thomson, “I like the slower approach,” and adds that something in her way of working allows her “to contact a lifetime of experience that I don’t even know is there. Putting one kind of non-color over another kind of non-color starts to bring in all kinds of familiar things, the imagery that wheels out is one of weather and humidity and time of year and wind direction—all of those things a person doesn’t think about that we walk in and out of every day.

Jane Wilson exhibits steadily until her death of heart failure in 2015. In her long career, she receives many honors and widespread recognition for her luminous works, which glean praise from an impressive roster of prominent critics. The following is a sampling of their responses to her work.

Michael Brenson, 1984: “In these landscapes…the intelligence and will of the artist are so thoroughly interiorized in the pictorial struggle that the paintings are experienced by the visitor well before and long after they are really seen.”

Paul Gardner: “In her own restrained way, without any pomp or puff, Wilson represents what the art world is about: staying power, whatever the trend of the moment, and a consistently developing body of work that results in a steadily increasing reputation.”

Luc Sante, 1997: “Any one of Jane Wilson’s paintings is a marvel; the effect of a roomful is extraordinary…Together, Jane Wilson and the sky have made an encyclopedia of moods and textures and marks and palettes, delineating the immense multiple personality we collectively name weather. The sky, which has no memory of its own, is tremendously fortunate to have her as its portraitist, its analyst, its biographer.